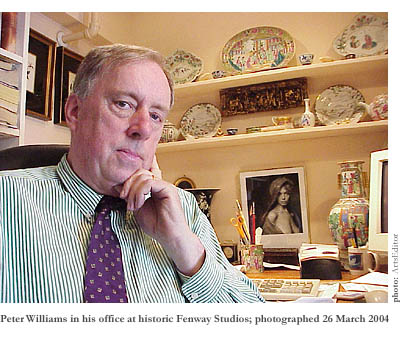

Peter Williams has a tendency to come and go. Ten minutes into the interview, as he’s about to explain the philosophy of art conservation, as opposed to restoration, he’s up attending another customer who’s come through the door of his studio. This becomes something like a ritual—a question is raised, a response pondered, his mouth opens, and then the front bell rings, meaning someone’s wanting to come in to the studio. Again. And he lurches out of the chair, hands me his résumé with a gesture that seems to mean all the answers are there, and walks down the hall while I set to work memorizing the pattern that adorns the inside door frame of his office for another fifteen or twenty minutes. Despite the tendency, I don’t think Williams is necessarily flighty, only concerned for his business. I overhear him downstairs, talking price with a customer who’s impressed with a painting. The price was a little too high—”I dunno, but if you still got it when I get back from Florida, I’ll take it.” And then the customer’s gone and Williams slumps back into his chair again to pick up where we left off. (Note: I tried hard, but never did get that pattern down.)

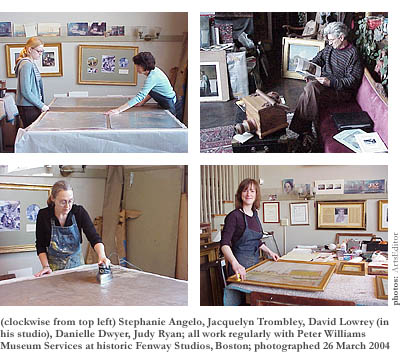

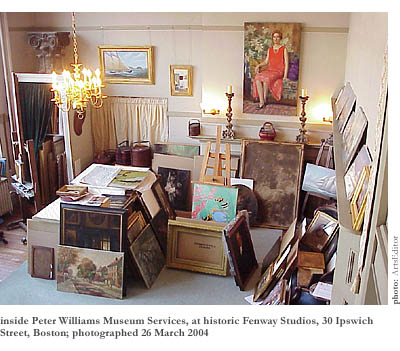

“Well, the preferred term now, I guess, is conservation,” Williams tells me, as opposed to “restoration.” Williams is the namesake behind Peter Williams Museum Services, a conservation/restoration service at the historic Fenway Studios building, 30 Ipswich Street, Boston. Most of the services offered fall under the heading of “cleaning,” but cleaning a painting or art object takes more than a dry rag and some Pledge. While Williams is seeing to yet another customer, his current staff—Stephanie Angelo, Judy Ryan, Danielle Dwyer, and Jacquelyn Trombley—see me through the process. The first step is usually to reinforce the canvas. Over time, the material goes slack and needs to be tightened. The staff takes the canvas off its frame and attaches it with conservation wax to a new canvas. They then subject it to a patented vacuum press that alternately heats and pressurizes the piece, fusing the two canvases and pulling the original one taut. The wax hardens over the back, keeping the newly retightened shape. If this sounds too much like an episode of Nova, bear with me. This is going somewhere.

Tightening the canvas pulls the aged—and, hence, solidified—paint back to its original space. If it cracks or comes off, Angelo, Ryan, Dwyer, and Trombley have to reattach it with wax. Once the canvas itself is secure, the actual cleaning takes place. The staff practices on the painting with different solvents. (“Can’t tell the recipe. Trade secret,” Trombley winks.) They remove the varnish, slowly and methodically, and, as each piece demands, rematch the colors of the original. They use modern materials to put color back into the painting, hence the job title “in-painter.”

This means that Williams’ distinction between “conservation” and “restoration” isn’t merely a piece of idle semantic stipulation. When a piece has been modified or altered by a later artist, even for the sake of cleaning, does it still represent what the original artist wanted? Is it that artist’s work? Or has it become a conglomerate piece? Is it still even the original piece?

“Well, there are a couple of principles,” Peter Williams starts up again, walking back into the office and resettling in his chair. “Don’t do anything you can’t undo. You want to be able to have somebody else undo it at a future date.” Is this laziness? Ass-covering? “You’re only the custodian for the art in your lifetime.” He cups his hands behind his head thoughtfully. “You leave it so that somebody else can come along and take apart what you do.” The difference between conservation and restoration finally comes down to how much a cleaner wants to put into a painting. “Restorers will embellish or make something up. With conservation, you preserve the original. You save as much of the artist’s intent as possible.” It sounds paradoxical, preserving a piece by altering it. Also, what if part of an object is missing, so there’s actually nothing there to conserve? Then, surely, you have to recreate something—not necessarily reinvent it, but it will be your own work. But then I’m directed back to that original principle. “Anything you do,” Williams reiterates, “you want to be able to undo.” Whatever change a conservationist makes, it must be impermanent. Yes, this seems to be the crux of the distinction.

Peter Williams started his career working at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, helping to clean paintings and objects. A graduate of Boston University, he had taken classes in classical art, philosophy, and archeology, and ended up restoring the largest Greek vase in America while at the museum. He soon opened his own shop out of an antique house in the South Shore of Boston. After having cleaned the largest Greek vase in America, he says, “I didn’t feel like I wanted to do anything less.” During his first years in business, he was approached by the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum to help repair objects from the desk of the former president that had been damaged after an exhibition tour. A painting from the king of Norway followed. Since then, he’s done restoration/conservation work for Boston College, private clients with displays at the Smithsonian Institution, the Swiss Ambassador to Japan, and the City of Boston. He has also worked with major commercial art galleries throughout New England and many historical societies and libraries, as well as art dealers and collectors. Williams’ shop since 1974 has been operating out of Fenway Studios, a historical landmark that was built in 1905 for the purposes of providing working space to the city’s artists and maintaining the “Boston School” of painting. The building is having an open house next month on May first and second from noon to 5 p.m. to give local art-lovers a chance to see the works of its artists and to find out, among other things, how a great many of them maintain the tradition of the “Boston School.”

His résumé is impressive, and it suggests the esteem in which Williams’ work is held. But the vast majority of jobs that come through aren’t the high-profile pieces. The staff tell me about the mostly decorative or sentimental nature of what they get. Family portraits, kitschy landscapes, and basic still-lifes make up the majority of the paintings they have to clean. Usually these things are just wall art that’s been passed down from generation to generation with no immediate historical value, just the owner’s sense of attachment. When I talk to Jacquelyn Trombley, she’s at work removing the varnish around the image of a stunted-looking bird. Trombley’s an artist herself, and when I ask her what effect cleaning images that maybe aren’t of the highest technical quality has on her own work, she laughs a little and says, “There are days when you come home and take a big, big brush and slap it against the wall, just to release the energy built up in the day.”

Trombley’s kind of short, self-effacing, a bit ironic, and also has a tendency to come and go. But, thankfully, she waits until we’re done talking before taking a smoke break. When describing her position she says, “I’ve been here the longest [since 1977]. I know where all the screwdrivers are.” But that belies her title and the respect the other staff members seem to have for her. She’s the Senior Conservator and does most of the cleaning.

“It’s tedious, frustrating work. You’re working intently with a great deal of purpose, and it has to look like it’s never been touched. You’re supposed to try not to leave a mark, but then nobody can tell that you even did anything,” she tells me, a little wistfully. There’s definitely a tension between what she’d like to do sometimes as opposed to what she has to do as a conservator. She adheres to the same principles of conservation as Williams does, but admits that sometimes you have to bend things or work around certain obstacles. “There’s a fine balance between what we can do [during cleaning] and what a client can afford. Sometimes we can make a painting look presentable, but we may not be able to do as much as we would like to. We also have to take the client’s taste into consideration.” Some customers don’t want a painting as clean as it could be, because the original color can come as a shock. If the piece is decorative, the old vibrancy can throw off the feel of a room. Trombley has her own rules as well. “We won’t change the color of the piece, we don’t destroy a signature, no moustaches, we don’t remove things…” She shares Peter Williams’ idea of impermanence, and is adamant that whatever limitations a client holds her to, she never does anything that a later conservator can’t take apart. The paint she uses for touching up a piece is synthetic and can be wiped out further down the road, and the wax and new canvas attached to the back can be heated and removed. So even if the line between the hand of the artist and the hand of the conservator does get monstrously blurred, the original object can be recovered. But the staff still makes a huge effort to “keep the ego out of it,” as Danielle Dwyer puts it.

“It’s tedious, frustrating work. You’re working intently with a great deal of purpose, and it has to look like it’s never been touched. You’re supposed to try not to leave a mark, but then nobody can tell that you even did anything,” she tells me, a little wistfully. There’s definitely a tension between what she’d like to do sometimes as opposed to what she has to do as a conservator. She adheres to the same principles of conservation as Williams does, but admits that sometimes you have to bend things or work around certain obstacles. “There’s a fine balance between what we can do [during cleaning] and what a client can afford. Sometimes we can make a painting look presentable, but we may not be able to do as much as we would like to. We also have to take the client’s taste into consideration.” Some customers don’t want a painting as clean as it could be, because the original color can come as a shock. If the piece is decorative, the old vibrancy can throw off the feel of a room. Trombley has her own rules as well. “We won’t change the color of the piece, we don’t destroy a signature, no moustaches, we don’t remove things…” She shares Peter Williams’ idea of impermanence, and is adamant that whatever limitations a client holds her to, she never does anything that a later conservator can’t take apart. The paint she uses for touching up a piece is synthetic and can be wiped out further down the road, and the wax and new canvas attached to the back can be heated and removed. So even if the line between the hand of the artist and the hand of the conservator does get monstrously blurred, the original object can be recovered. But the staff still makes a huge effort to “keep the ego out of it,” as Danielle Dwyer puts it.

What maybe makes Williams’ shop unique is its emphasis on employing artists as opposed to a team of chemists or technicians, the other popular choices for conservators. Everyone currently on staff is involved in art production in some way. Trombley experiments with works that explore painting as sculpture, Dwyer works in oils with ideas about testing the less linear paths of contemporary art, and Angelo fuses a Pop Art aesthetic into works on feminine identity. Ryan is a painter as well, and then there is Williams’ work: maritime paintings.

Using artists instead of chemists to clean paintings is a fairly conservative move. It seems more radical—using painters to retouch or repaint a piece sounds a lot like restoration, in fact, but then we come back again to Williams’ rule #1: leave it so someone else can undo it. The original painting remains intact. New solvents or processes run the risk of obliterating the object. “Our techniques are time-tested,” Trombley says. “We just don’t trust high-tech, cutting-edge chemistry. You never know what’s gonna happen.” So a possibly cleaner piece is the loss; the gain is the structural integrity or existence of the artwork and the artist’s intent.

Everyone in the studio agrees that having a working knowledge of painting helps in the conservation effort for the simple reason that conservation of this sort requires in-painting. But does the door swing both ways? “It gives you a good idea of the history,” Stephanie Angelo says. “You get exposed to so many different works, you can see what worked and what didn’t.” She and Dwyer share in the assessment that the vast majority of works they see…uh…didn’t work. So it’s learning by negative model. But the plus side is a greater understanding of the materials. Both say that they’ve obtained an expanded idea of color mixing.

After another twenty minutes of waiting, Williams comes back to see me off. He tells me that I should check in on David Lowrey, another artist at Fenway Studios that he has a working relationship with. I climb the stairs and walk into a studio that contains ornate handmade puppets, masterful working replications of 17th and 18th Century camera obscuras, and a man who looks eerily like poet and playwright Samuel Beckett (shock of high hair, six-foot frame, long face and all) bent over a picture frame, chiseling designs into it. Lowrey handles a lot of the frame restoration for Williams and the object rebuilding that other staff doesn’t do. The visit to his studio is a kind of coda to meeting with Peter Williams and his staff, and it’s hard not to be awed by the many crafted objects arranged along the walls. It’s also hard not to be charmed by David Lowrey and his enthusiasm for history. While working on the frame, he spools out information of all kinds about the 17th Century painter Johannes Vermeer, the camera obscura, Renaissance humanist thought, the affinity between restoration and conservation, and the wisdom of an unnamed Parisian striptease artist. He pulls himself up for a second. “She said,” and here his eyes widen as he lapses into a mock-French accent, “‘I be real; I try to conceal.'” He chuckles and bends back to the frame. He chisels some more and blends the new design, done in cast plaster, into the existing carving. Then he tells me another story about Shakespeare.