Juan José Barboza Gubo didn’t think of himself as a painter until about a year ago. The 26-year-old Peruvian artist, living in Somerville on a student visa, made a name for himself as a sculptor back home in Lima. A 2000 recipient of a BFA from Pontifical Catholic University, he has been contributing his extravagant sculptures to group exhibits at galleries and museums in Peru, as well as to sacred and secular public spaces, since 1997. Some of the latter depict Saint Leopold, the Virgin Mary, and Mother Teresa de la Cruz in manners agreeable to church authorities; some of the former, erupting uncensored from the subconscious, depict a hermaphrodite angel, a masked bishop cradling a two-headed mooncalf in his arms, and an Incan warrior in place of Jesus on the cross. Evolving from neatly rendered preparatory color illustrations that reveal Gubo’s buena mano at draftsmanship—”We call it having a good hand in Peru,” he says—the sculptures are curious, colorful, and grotesquely graceful enough to have earned Gubo commissions on his new work. So sculpture has been his thing. Yet now he finds himself spending a roughly equal amount of time on painting, and has already done it so dynamically that Mark Gallery in Cambridge has agreed to include him as half of an upcoming two-man exhibit—Earth Vibrations, from 19 October to 22 November—that will also feature the Raku pottery of Ken Parsons.

Though it could probably get him the steady commissions that would earn him the work visa he desires, Gubo hasn’t turned to painting beatified icons for the Roman Catholic Church; nor has he simply adapted the distinctly Latin American imagery of his sculptures to the two-dimensional realm of the canvas. (He reserves for his three-dimensional work representations of the twisted mess made when icons of Catholicism crash into icons of pre-Hispanic art.) Among his paintings there are no felt spray-canned features of red-skinned, black-haired cherubs with wings of red and gold feathers like those found on a plumed serpent. He’s not copying the melted clocks of Salvador Dali, the serene socialist murals of Diego Rivera, or the tortured, magically unrealistic symbols of Frida Kahlo and Remedios Varo. Rather than rely on the written wonders of Pablo Neruda and Gabriel Garcia Márquez for advice, he’s incorporated imagery from two pre-Columbian Inca cultures—the Mochica (or Moche) culture of Christ’s time and the Paracas culture of a few short centuries later—in dazzling, irregularly geometric, practically protean designs that urge to ooze beyond the borders of the canvasses they fill.

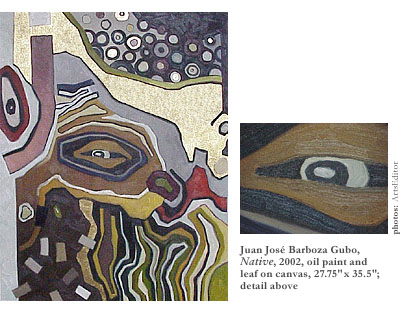

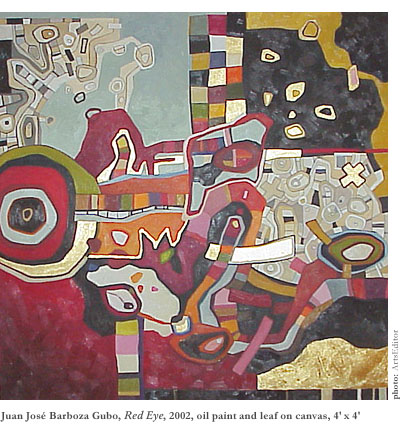

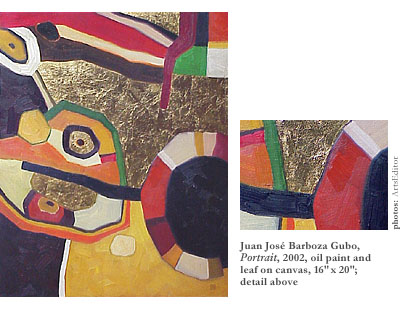

From the symbolically decorated Moche pottery, Gubo has taken serpentine imagery common to much of the Mesoamerican art still visible among the ruins of the three umbrella empires (Maya, Aztec, and Inca) on the tourist trails of Mexico and Central and South America. Snakes, or bits and pieces and suggested forms and patterns of snakes, are everywhere in his paintings, sometimes manifested as belts of variegated bands winding toward the middle of the picture from outside the painting, other times as sinuous, suggestive images underlapping and overlapping other abstracted images and serving to isolate certain portions of the plane from others. Eyes, too, abound—each one consisting of mosaic-like panels of color, and most of them only loosely related to the animal forms they come from. “You see images of the eye in all the pre-Columbian art,” notes Gubo. Is it the eye of a compassionate god or the eye of the ravenous, death-sick, animist spirit—or are these deities one and the same? Here’s a royal-blue, blood-red, and tooth-white eye symbol at the end of one of the serpentine shapes that is made up of bands of olive green, orange, lime green, and maroon. The serpentine image is paralleled and contrasted by a sunny yellow band that has a white border—and near the edge of the white border runs a series of variously colored dashes (blue, gold, and orange, for example) that itself is connected to another image of an eyeball, this one with a red pupil, a blue retina, and two or three more rings of dashed colors—easy to miss until a third or fourth inspection of the overlaid details—that create a quiet cacophony against a midnight blue background. “Those,” explains Gubo, looking at the colored dashes that appear in all of these unusual paintings, “represent drops of blood.” The decoded visual language of the Mesoamericans speaks in bold terms of earthly horrors.

While the iconographic Moche imagery dominates the paintings, ornamental imagery from the telas, or textiles, of the Paracas people provides visual balance, filler, and an additional element of mystery. A checkerboard pattern of subdued, earthy colors—brown, red, yellow, black, and something pretty close to pink—occupies a quadrant of one feverishly allusive painting. Three creepy eye images lurk nearby, of course, looking directly this way and maybe right through us, while the checkerboard pattern waits quietly to be admired, a humble exhibition of beauty for beauty’s sake, without symbolic meaning. A large, less congested area underlies another quadrant of the painting, just the other side of the neatly chaotic jumble of eyes, blood dashes, and banded serpents. It’s got a cluster of crosses on it, the only allusion besides the occasional horse image to post-conquest history, and there’s a variegated band of Paracas checks along the border. Look around the fascinating surface of the painting again, and here comes a winding serpent clear down toward the bottom, slithering its way inconspicuously toward the neat mess Gubo has made in the middle of the canvas. The agonized horse’s head, somewhat out of Picasso’s Guernica, bared teeth and all, finds itself of equal importance to the rectangular patch of checks and the flower-like growth of eyes. And somewhere in the middle of it all there’s often a gray, white, and black puzzle of eye and serpent shapes, too. Not much color in that part-the only part that doesn’t have much. Why is that? Is it just rest for the viewer’s eye, or an allusion to a design Gubo’s admired from Moche pottery?

“I try to work with a lot of things in one painting,” says Gubo. Seen up close, each painting is an intricate arrangement of flat color-panels on a flat plane, with no shading to speak of—a colorful, geometrically warped fluid that has congealed on canvas. “I use many colors in one piece,” he points out, “and lots of details, and I put them all on one surface, so that it’s sometimes hard to tell the foreground from the background.” Seen from slightly farther away, each painting looks like a glorious puzzle spilled fully-formed from Gubo’s imagination—not a puzzle pieced meticulously together by hand so much as poured from the head. In light of this, the Spanish word for jigsaw puzzle, rompecabezas, translated literally as “broken heads,” seems to speak to the “systematic derangement of the senses” that French symbolist poet Artur Rimbaud advocated for the creation of poetry and visual art.

Mixing iconographic Moche and ornamental Paracas elements, as well as natural, earthen colors such as reds, browns, and ochres with brighter modern colors, and stirring them together in a crowded collage that nevertheless respects and preserves the identity of each image, makes the making of rompecabezas an adventure. Gubo enjoys putting them together at least as much as his viewers may enjoy being dazzled by their spectacle. But he still has the sense that this year of experiments in painting is just a start. “I am trying to find a form that can accommodate all of the images and symbols from the pre-Columbian cultures I am interested in,” he admits.

Kay Meckes, speaking both for herself and her husband, Mark Gallery co-owner Jeff Dowler, couldn’t be much happier to support Gubo’s evolving effort to find this ideal form. “Juan is so good and talented,” says Meckes, “that he’s sure to go somewhere.” For the moment, it would seem an enviable honor to be part of a two-person exhibit at a gallery in the cultivated Huron Avenue district of Cambridge. Meckes and Dowler opened the gallery this past January, a number of years after starting to buy art with disposable income. “We dreamt of opening a gallery a long time ago,” Meckes says. “Over the years we’ve gotten to know and admire a lot of artists and have hoped to show their work for them.” It’s an aesthetic endeavor for them first, and a business endeavor second, and Gubo’s work rests well with both endeavors. But Mark Gallery also seems to be an effort to contribute to the surrounding community. Meckes notes the presence, in the immediate vicinity, of various shops—an interior decorator, an antique dealer, and fellow entrepreneurs in the home furnishings business, not to mention a fancy trattoria, a pretty good pizza parlor, and a highly respected artisan bakery—all survivors of the legendary Sage’s grocery store that closed a few years ago.

Which leads one to wonder. First, does such painting, without a real ending or beginning, with no real top, no real bottom, and a background that’s up for debate, seem suited for a conventional landscape or portrait shape, especially when its turbulent forms seem ready to burst beyond the confines of the canvas? Don’t the paintings seem destined for mosaichood and muraldom? They’re great to look at on their own, yet can be seen as studies for larger works in the same way that Gubo’s picture-perfect colored-pen illustrations are studies for his sculptures. Second, can Gubo’s paintings, embodying gruesome images that tell of human sacrifice, voracious earthly fecundity, and hallucinogenic vision quests into the hellish heart of humanity, really “go” with the décor in a typical Cambridge family’s home? If the home already accommodates its share of fashionable furnishings from cultures less particular than our own, probably the answer is “yes.”