Sculptors—not just site-specific installation artists working three-dimensionally in multiple media, accompanied by improvisational orchestras of wind gusts, street noises, and basso profundo gastrointestinal outbursts, but old-fashioned modelers of busts and figures as well—haven’t generally gotten the kind of acclaim painters have. That’s why Donald Judd (1928-1994), among the country’s foremost three-dimensional artists of the post-Kennedy era, continues to go without much of a name in art-literate households that don’t shelter Bauhaus architects and appropriate-technology engineers. How else to explain why one worldly citizen, a learned book designer unable to place the name, wondered in jest if Donald Judd is related to Winona and Ashley? Or why another, a children’s art psychologist, admitted that her erudite coiffeur stumped her completely with a reference to Judd’s work while sculpting her do, prompting her to go online as soon as she got home to see what she could find by the artist on the Internet—much of it, in her opinion, frankly a bit tiresome. Or why yet another, a contemporary art collector, couldn’t remember who Judd was either.

Judd never had the appeal of some considerably less unknown artists whose primary genre was sculpture (a word that he detested as much as the word “minimalism” that many attached to him). His freestanding perfectionist “units” of cubes, slabs, rectangles, and tubes sometimes benefited greatly from brilliant coloration and had an air of divine mystery to them when they worked. But he was never as accessible as the others were. Earthy old Henry Moore, for example, shaped organic bronze forms—some more suggestive of the human female form than others—that can be seen, noticed, and sat upon on college greens the world over without too many people walking up and saying, “Yes, but is it art?” Claes Oldenburg created enormous, colorful, “soft” sculptures of mundane icons—hamburgers, clothespins, lipstick tubes—as accessible to wide-eyed children eating Pop-Tarts as they are to critics writing about the Pop Arts. And David Smith, the self-proclaimed workingman’s sculptor, made iron constructions—beams, disks, rods, crescents, and cones welded together in sums that were greater and more representational than their parts—that exist half in an abstract universe of pure mathematical form and half in the flesh-and-blood world, and not too much in either world to exclude much of anyone.

Of the three sample sculptors described above—representative (and to varying degrees representational) of diverse artistic experiments that were conducted during the latter half of the 20th century—David Smith most closely resembled Donald Judd. In fact, Judd considered Smith’s ironically bittersweet ironworks the last solid sculptures worth looking “at” from that void known as space. A prolific critic for high-profile art journals since his graduate-school days at Columbia University, the heady and terse Judd asserted that “vertical, anthropomorphic, totemic sculpture” was no longer relevant. With the new stress on space and environment in experimental art (dance, architecture, and music included), there wasn’t room anymore for symbolic monuments to human egocentricity. No room, even, for representational art, period. As might be apparent in his ambitious development of environmental art parks on tracts of rural land in Texas and Europe, Judd wanted art to relate to and be accommodated by its immediate environs, even if with its multitude of straight lines it resembled nothing in nature. Painting was dead, according to Judd; space and color were both “new in art,” and yet to be blessed with a critical vocabulary; and his own sometimes mystifying industrial-arts objects, as sure to please an engineer as an artist, would rely for their aesthetic success as much on the space around them (especially the permanent outdoor works) as they would on their own curious forms.

Relatively speaking, there was never a shortage of opportunities to see Judd’s indoorsy work. His stacks of anodized and colorized aluminum “units” and his wall-mounted, plywood boxes (always complicated by optically ambiguous geometric constructions such as panels or cylinders or ramps) probably didn’t show up much at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, notorious until recently for its disregard of contemporary art. But Judd pieces appeared frequently in edgy group and solo exhibits in New York and Europe. His better-known work includes odd stacks of copper or painted-aluminum units that he affixed to gallery walls like shelves at nine-inch intervals—their polished copper, cadmium red, brilliant bronze, or emerald green surfaces gleaming with superior intelligence. A big brass lidless cube with a green Plexiglas interior inviting the gallery-goer to walk across the space for a contemplative glance within. A copper box with a red Plexiglas interior and a slanted copper shelf partially—and cryptically—obscuring the view of the delectable red. And a set of six plywood boxes on the wall with green Plexiglas backings and six different patterns of plywood lattice-work obscuring only partly the ever-more tempting view of the delectable green.

Relatively speaking, there was never a shortage of opportunities to see Judd’s indoorsy work. His stacks of anodized and colorized aluminum “units” and his wall-mounted, plywood boxes (always complicated by optically ambiguous geometric constructions such as panels or cylinders or ramps) probably didn’t show up much at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, notorious until recently for its disregard of contemporary art. But Judd pieces appeared frequently in edgy group and solo exhibits in New York and Europe. His better-known work includes odd stacks of copper or painted-aluminum units that he affixed to gallery walls like shelves at nine-inch intervals—their polished copper, cadmium red, brilliant bronze, or emerald green surfaces gleaming with superior intelligence. A big brass lidless cube with a green Plexiglas interior inviting the gallery-goer to walk across the space for a contemplative glance within. A copper box with a red Plexiglas interior and a slanted copper shelf partially—and cryptically—obscuring the view of the delectable red. And a set of six plywood boxes on the wall with green Plexiglas backings and six different patterns of plywood lattice-work obscuring only partly the ever-more tempting view of the delectable green.

Donald Judd’s outdoor pieces can be seen, if not readily discriminated from the functional architectural features of their surrounding urban landscapes, all over the world still. Concrete labyrinths to get lost and found in. Concrete rings to sit by a lake on, with corresponding rings lower to the ground and parallel to the slope of the shore to stimulate contemplation of geomorphic contours. Open-ended steel or concrete cubes as large as those sewer-pipe joint-housings you see at major construction sites, but bisected by door-like panels, pillar-like cylinders, or ramp-like slabs. A summer vacation could probably be planned around visits to these permanent Judd installations.

Meanwhile, though, Judd’s indoorsier work can be seen through March 19th in the exhibit Donald Judd: Editions: Prints and Sculptures at the Barbara Krakow Gallery, 10 Newbury Street, Boston. Into the fifth-floor showroom, just off the elevator, the endearingly enthusiastic crew of dedicated Juddheads has dragged selections from the gallery’s precious inventory. The relatively edgy gallery deals in minimalist and conceptualist art by name-brand artists, at the exclusive prices expected of the galleries on the same block as The Ritz-Carlton. During the exhibit, the gallery will be trying to sell off selections from its inventory of Judd’s artwork, including not only two three-dimensional aluminum pieces that are recognizably Judd, but a relatively small selection of his works on paper as well. A public-minded artist such as Judd may have had mixed emotions about the art business—just as an environmental artist such as Judd may have had mixed emotions about showing his work in swank retail galleries—with his works going for as much as $35,000 a piece in this exhibit. But given the community-outreach efforts of his Chinati Foundation in the rurally poor Marfa, Texas area—including educational programs for children whose parents might find non-representational art puzzling at best—maybe these sins are forgivable.

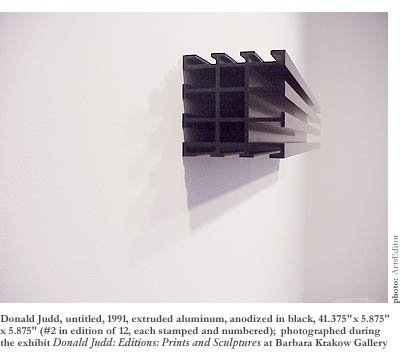

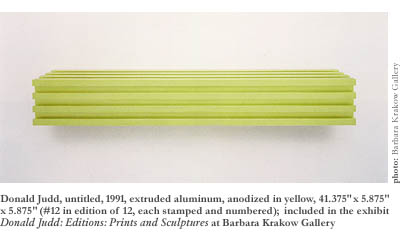

To the first-time beholder of Donald Judd’s work, the Barbara Krakow Gallery’s exhibit of his adventures in shape, color, surface, and volume might seem a little less than generous in spirit than Judd’s paradoxically humanist ethics would suggest. With patience and open-mindedness, though, the same beginner might find the work yielding more pleasures than initially apparent. The extruded aluminum pieces, one anodized in yellow and the other in black, identical in form, wait impassively to be seen at eye-level on the white wall. Horizontal lengths exactly 41 and three-eighths inches long and 5 and seven-eighths inches deep and wide, they might be mistaken for beams stolen from the construction site where a pretty postmodern structure is going up, or for parts extracted from an enormous computer. They betray no narrative or symbolic traits, and they barely exude any atmosphere or bristle with mysterious energy and beauty—unlike, say, an untitled orange cube he once designed, with a smooth gray trench cut in the top for a pipe, or the corresponding plywood box he designed separately, with a gray aluminum pipe fitting snugly into that cut. The monochromatic beams on display at the Barbara Krakow Gallery are given curiosity, if not much power to satisfy it, by the inexplicably complex indentations of form, which in Judd’s case is always indistinguishable from content. It would be kind of cruel, not cruel but kind, to call these pieces “gizmos”—like parts of a mechanically-inclined child’s model construction set.

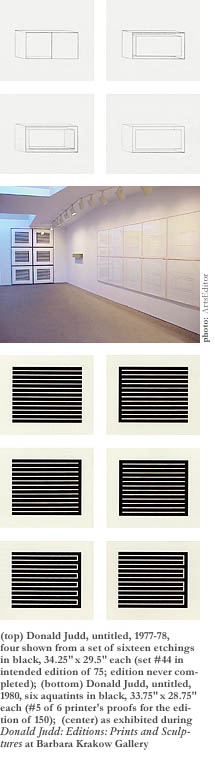

Though it would be nice to see at the Barbara Krakow Gallery the more interesting Judd work that can be seen in glossy catalogues and big-city museums, it’s instructive to the curious observer to see his secondary creations. If nothing else, a visit to the gallery could easily inspire an appetite for the well-known Judd work. And if the two aluminum pieces currently on exhibit don’t intrigue the gallery visitor as much as some of the well-known Judd work, an investigation of the aquatints and the etchings on view might. These involve enough magically mathematical plays on simple designs to keep a person busy for an hour. Excellent examples of Judd’s fascination with repetition, seriality, progression, and geometry, and of his love of what he called “the charm of the play between voids and solid spaces,” these permutation-happy pieces demand quiet contemplation from a comfortable distance. In the untitled set of six aquatints (three rows of paired images), Judd has made six discrete patterns of black and white horizontal bands that on first impatient glance look identical. A closer look reveals that each does indeed have thirteen black bands of the same width, but that each pattern differs distinctly from the others. One print, the simplest, consists of freestanding bands without borders—just thirteen black bands on a white background. The one next to that consists of bands connected by a black border in the white left margin, like a mutated uppercase E. The second row pairs a pattern with a black border in the white right margin (a mutated uppercase E transposed); the second one in the second row has borders on both sides, like an abstracted blueprint for a washboard. And the two in the bottom row have mind-boggling, labyrinthine designs that are embarrassingly difficult to reproduce on paper. What appear on first glance to be six identical patterns turn out on closer inspection to be like six bars of music in a visually rhythmic score that a person could play on an instrument.

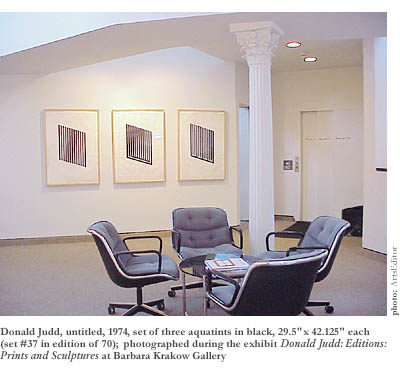

The other two works of Judd’s graphic art on display at the Barbara Krakow Gallery corroborate the distinct impression that Judd was happy to be all form and no representational content, all math and music and no culturally loaded symbols. His untitled set of three aquatints in black offers three variations on the bars-and-borders pattern, abstracted E-like images this time turned on their backs with their legs in the air and arranged at a 45-degree angle that slides the eye along the smooth soles of their feet down to the lower right. His sixteen etchings of a long box—roughly the shape of a blanket chest—with illusory, shifting planes that pitch the eye backward and forward in space in confusion over perspective and geometric shape, offer the amateur math fan an opportunity for extended contemplation that there may not be time enough in a day for thorough understanding without the expert technical assistance of a carpenter.

Given all this ethereal erudition, it’s unlikely that the Platonically idealistic artist Donald Judd was related to Ashley and Winona, but only the professor’s hairdresser knows for sure. He, not the designer, psychologist, or collector, is the unpredictable one who has actually collected some of Judd’s work in his home.