Who would ever dare to recycle the 1975 Doubleday/Anchor edition of The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke? Surely only someone who’d long since replaced that $3.95 paperback with a newer edition, the likes of which I have not even seen or bothered to look into, suspecting that the poems have not been revised posthumously.

I don’t mind the dated cover graphic of the little yellow sun-blob above a row of four blobby trees, one taller yellow and one taller blue tree (crowns vaguely linden-like) flanked by smaller green blob trees, perhaps coniferous cedars. I’ve hung onto my 20-something paperback Roethke, repairing its broken back several years ago with chiropractic Scotch tape, continuing to leaf through it now and again to read an old favorite, sometimes to my nature-loving wife, who teaches high-school English, but usually to myself. The book has served me well since I bought it in 1976, at the Grolier Book Shop in Cambridge I believe, the year I moved to the Boston area from the Appalachian Ohio state-college town where I had gone to school. It serves me well still.

But somebody around the corner from me on Henry Street in Cambridgeport-let’s say a woman around my middle age who does publicity for a nonprofit international development agency-threw her copy out. Let’s assume, perhaps wrongly, that she didn’t replace her copy either, finding Roethke a bit too apolitical, and that she hadn’t read this one in so long-not since the course she took at Brandeis on modern poetry-that she just figured she may as well get rid of it.

I found it where she’d left it on a recent rainy night in November when I was out for my nightly walk. She had placed the Roethke neatly atop a stack in the blue plastic bucket the city provides for recyclable materials. In the morning it would be whisked away to the central distribution center, and driven from there, probably, out Route 2 to the paper mill in Irving, soon to be converted to the paper product writers most fear being remaindered to. Roethke had not been thrown out in the trash, exactly; there was some concession in the promise of being converted.

By drizzly yellow streetlight, with my eye out for the re-usables I sometimes collect-little white metal three-shelved storage cabinets good for stashes of gardening supplies; wicker-work wastebaskets with frayed reeds; slightly decrepit shower racks for hanging soaps and shampoos from-I spotted him like an old friend I once knew so well that I hardly have to speak with him now to know what’s going on with him. I can tell just by looking whether he’s keeping himself in shape, being productive, having a happy home life. And Roethke, on first appearance on top of that stack, looked just fine. I reached for the book instinctively as if to shake the old friend’s hand (someone I don’t even hang around with anymore) and was picking it up to look at it (even though I had a friend just like that at home) when this analogy died of natural causes.

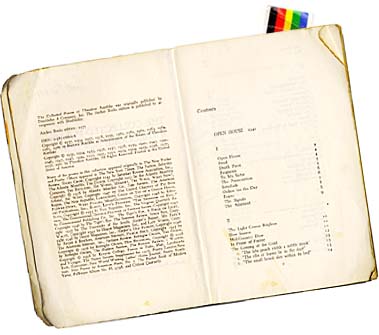

The book fell open to the table of contents and its 23-year chronology of Roethke’s writings. I noticed the date (1941) of his first book, Open House, and its five sections of lyrical poems, measured, I remembered, by rhyme and meter, a lot of them full of Roethke’s familiar affection for nature and his somewhat preachy disgust with human folly; predictably Romantic in sentiment perhaps with its longings for release to the animated otherworld, yet relieved by frequent surprises of elated expression. First I read a few lines from “Long Live the Weeds,” a poem, titled after a line in Hopkins, that illustrates his lifelong effort at primal release and identification with nature:

Long live the weeds that overwhelm

My narrow vegetable realm!

The bitter rock, the barren soil

That force the son of man to toil;

All things unholy, marred by curse,

The ugly of the universe.

The rough, the wicked, and the wild

That keep the spirit undefiled.

With these I match my little wit

And earn the right to stand or sit,

Hope, love, create, or drink and die:

These shape the creature that is I.

Next I couldn’t resist reading, right there in the rain to see what it had to offer, “The Reminder,” the first of several poems he would publish about his Prussian-immigrant father:

I remember the crossing-tender’s geranium border

That blossomed in soot; a black cat licking its paw;

The bronze wheat arranged in strict and formal order;

And the precision that for you was ultimate law;

The handkerchief tucked in the left-hand pocket

Of a man-tailored blouse; the list of shopping done;

You wound the watch in an old-fashioned locket

And pulled the green shade against the morning sun.

Now in the misery of bed-sitting room confusion,

With no hint of your presence in a jungle of masculine toys,

In the dirt and disorder I cherish one scrap of illusion:

A cheap clock ticking in ghostly cicada voice.

I liked the precise particularity of those images-geranium, cat, and wheat-recollected from early childhood in “bed-sitting room confusion”; the focusing apostrophe to the unnamed father figure and the denial and doom suggested by the winding of the watch and the pulling of “the green shade against morning sun”; and the prosodic pun on his rhymed and metered lines in his description of the “strict and formal order” of the wheat. The poem worked for me as a concise and pointed catalogue of poignant images, and also because it reminded me of a poem from his second book, The Lost Son and Other Poems (1948), that I’d turn to next: “My Papa’s Waltz,” without a doubt his most anthologized poem, written in a similarly respectful but damaged spirit about the man who “beat time on my head/With a palm caked hard by dirt,/Then waltzed me off to bed/Still clinging to your shirt.”

Before I continued along the sidewalk to the river for a look across the water at the fogbound skyscrapers of Boston, I checked the rest of the paper tower rising from the blue recycling barrel on Henry Street. My distant neighbor-maybe not a Brandeis grad after all but a town-meets-gown city councilor guy too busy debating zoning issues to read much poetry-had also brought up from the mildewed basement (for now I sniffed a familiar must) his archive of paperback-leftist political philosophy books. From Hegel to Marx. Revolt of the Masses. One-Dimensional Man. All of them easily converted to toilet paper.

I first heard of Theodore Roethke in a survey class on poetry at Ohio University in the early 1970s. The professor, Stanley Plumly, a stylish man by then already the accomplished author of Out-of-the-Body Travel, turned us on to many of the greatest hits of the canon-from Shakespeare and Dickinson to Ransom and Ginsberg-with ardent enthusiasm for the indelible feats of language recorded in the cloth edition of a generic anthology no doubt long out of print by now. A native of the foothills of Southeastern Ohio, Plumly adored the bucolic. He has written some beautiful poems about Keats since then, and he loved how Ransom in “Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter” described some geese flying under the sky. He admired the devotional gushes of anapestic consonance in Hopkins, and he appreciated the unchecked flow of enthusiasm in the long and sometimes hilarious lines of Ginsberg’s “America.”

I don’t recall exactly which of Roethke’s poems appeared in that anthology. (I still own the book, by the way; but I’m 200 miles away from the shelf it’s on now.) But I do recall that we read the obligatory “My Papa’s Waltz” as a prime example of Roethke’s control of form and tone. I’m sure we read the hallucinatory recollections (fitting for our psychedelic pastimes) in the title poem of The Lost Son and Other Poems, getting off on its dark children’s ditties -“The weeds whined,” goes one quatrain, “The snakes cried,/The cows and briars/Said to me: Die.”-and its troublesome notational utterances that sound, we probably said, like Eliot on acid:

What a small song. What slow clouds. What dark water.

Hath the rain a father? All the caves are ice. Only the snow’s here.

I’m cold. I’m cold all over. Rub me in father and mother.

Fear was my father, Father Fear.

His look drained the stones.

Maybe professor-poet Plumly, ruggedly handsome and hip with thick wavy hair at the head of the class, told us that these two poems, “My Papa’s Waltz” and “The Lost Son,” represent the extremes of style between which Roethke usually worked in his several succeeding collections of poems. He also must have introduced us to the two outstanding sequences of poems that Roethke is perhaps best known for: the so-called “greenhouse” poems written early in his career (from The Lost Son and Other Poems) and “The North American Sequence” written toward the end of it (from The Far Field, 1964). For these have been the poems I’ve returned to frequently since then for an experience of the sublime. I read the compact and explosive descriptions of the greenhouse poems for almost no other reason than to enter the root cellar at his family’s nursery in Michigan where

Bulbs broke out of boxes hunting for chinks in the dark,

Shoots dangled and drooped,

Lolling obscenely from mildewed crates,

Hung down long yellow evil necks, like tropical snakes,

And what a congress of stinks!

I loved-and love-how the orchids, in another brief and delicious greenhouse poem, “lean over the path,/Adder-mouthed,/Swaying close to the face,/Coming out, soft and deceptive,/Limp and damp, delicate as a young bird’s tongue”; the tangible memories, in “Moss-Gathering,” of “the crumbling small hollow sticks on the underside mixed with roots,/And wintergreen berries and leaves still stuck to the top”; and his confession that after he “plunged to my elbows in the spongy yellowish moss of the marshes” and ran off with a rug of it, “the kind for lining cemetery baskets,” he “always felt mean…./As if I had committed, against the whole scheme of life, a desecration.” In “Big Wind,” “Child on Top of a Greenhouse,” and “Frau Bauman, Frau Schmidt, and Frau Schwartze,” he exults in recollected experience of his green childhood, like an American Wordsworth but with the ultimate effect of seeming to be-as someone, maybe Seamus Heaney, has said-not so much about nature as they are of nature. The protean sense of “all things innocent, hapless, forsaken” (from the later poem “Meadow Mouse”) sprouts from the particularity of minutely observed and empathized images and from the unchecked presentation of them, without argument and irony that might drain the color from them. “Nothing would give up life,” he writes at the end of “Root Cellar.” “Even the dirt kept breathing a small breath.”

Roethke extended his formal wings in the six poems, equally descriptive and exalted, of “The North American Sequence.” Maybe they are odes. The lines are long. Each poem consists of several strophe-like sections. The liberty to make the brazen prophetic announcement is more often taken now, as is the liberty to extend metaphor to the metaphysical. “In the long journey out of the self,” he writes, taking a line-break, “There are washed-out interrupted raw places/Where the shale slides dangerously/And the back wheels hang almost over the edge/At the sudden veering, the moment of turning.” Again, he is not afraid of the extravagant statement: “The self persists like a dying star,/In sleep, afraid. Death’s face rises afresh,/Among the shy beasts, the deer at the salt-lick,/The doe with its sloped shoulders loping across the highway,/The young snake, poised in green leaves, waiting for its fly,/The hummingbird, whirring from quince-blossom to morning-glory-/With these I would be.” His surrender to the elemental recalls an ecstatic dithyramb from oral tradition, while his control of form and tone and the particularity of his images perpetuates the best of the more recent-sorry for the pun-anal tradition of the printed word. He shows us “the ice piling high against the iron-bound spikes” along a river in the Pacific Northwest where the sequence takes place, “Gleaming, freezing, hard again, creaking at midnight,” a sound that makes him “long for the blast of dynamite,/The sudden sucking roar as the culvert loosens its debris of branches and sticks,/Welter of tin cans, pails, old bird nests, a child’s shoe riding a log,/As the piled ice breaks away from the battered spikes,/And the whole river begins to move forward, its bridges shaking.”

Unlike most of his prominent-poet peers, Roethke sought a kind of salvation and surrender of the individual self in the physical world. While the others were agonizing over their social status, Roethke was attempting to “animalize, vegetablize, and mineralize” himself-to borrow a phrase from a Galway Kinnell elegy to James Wright-and hurl himself headlong, on the momentum of his poems, from agony to ecstasy. There was something truly atavistic and primal in his impulse, because “going back to nature” wasn’t quite yet the thing to do. (He was said to eat raw meat on occasion to keep in touch with his animal nature, and the picture of him in the Naked Poetry anthology depicts him in a sort of wandering sage’s robe.)

Roethke taught at the University of Washington in Seattle. He was a talented tennis player (according to a friend’s father, who had him for freshman comp at Penn in the ’40s). These are the credentials of a bourgeois academic, for sure. And yet he wrote like a drum-beating wild man and had an unfortunate need to check into the psychiatric ward on occasion to check his mania. His last poems take after the litanizing Whitman and make way for the Deep Image movement of the ’60s-yet he continued to acknowledge T.S. Eliot as the master. It’s Eliot’s advice from the sublime Four Quartet that Roethke’s answering, with decisive concision, at the end of “The Longing”:

Old men should be explorers?

I’ll be an Indian.

Ogalala?

Iroquois.