Run Your Own Letterpress Shop! Immediate opening. The ideal candidate will have, at a minimum: excellent design and layout skills; interest in problem-solving; innate mathematical sensibility; ability to work with extreme precision and recognize the most minute error; a carefully cultivated appreciation for typography, design, and printing history; talent for improvising mechanical repairs to finicky old equipment; ability to deal well with difficult clients; and a stash of money to spend on procuring, repairing, and storing equipment, buying materials, and running the business. Good stress management skills necessary. Patience in large amounts a must.

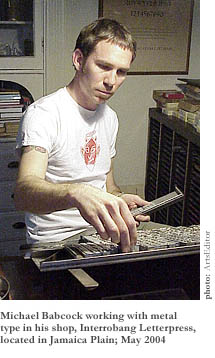

It’s almost as though Michael Babcock answered an ad to do what he does. As owner and sole employee of Interrobang Letterpress in Jamaica Plain, Babcock spends his nights and weekends creating compositions, setting metal type, and guiding paper through the presses. But the letterpress is not as simple as a series of repetitive motions. It’s a conglomeration of intricacies, a 550 year-old technique with many pitfalls and a steep learning curve.

It’s almost as though Michael Babcock answered an ad to do what he does. As owner and sole employee of Interrobang Letterpress in Jamaica Plain, Babcock spends his nights and weekends creating compositions, setting metal type, and guiding paper through the presses. But the letterpress is not as simple as a series of repetitive motions. It’s a conglomeration of intricacies, a 550 year-old technique with many pitfalls and a steep learning curve.

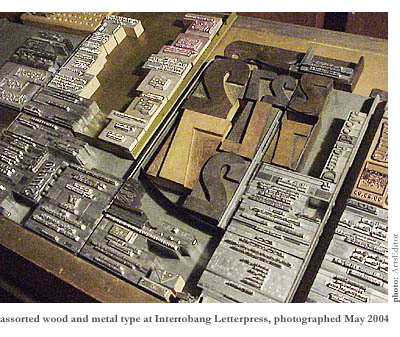

In traditional letterpress printing, raised type (usually metal, sometimes wood or hand-cut linoleum) and engraved plates bearing illustrations or other art are fitted together within a metal frame called a chase. Paper that enters the press is rolled or compressed directly onto the inked composition. In the final piece, non-printed areas are raised above the printed impression. Inconsistencies in plate or type height are evened out by “packing” a sheet or two of smooth paper under the plates where necessary. It’s a very high-quality, tactile printing method, and it’s revered for its clean lines and superb reproduction of detail.

You don’t enter the craft of letterpress to make a few extra bucks or nurture a romantic artistic inkling. In fact, in today’s digitized, every-tool-at-the-ready design environment, where anyone with a computer and some standard software can do both with a minimum of money, time, and space, you’d have to be a very serious fan of the medium, and the owner of a colossal work ethic, to even consider surrendering large chunks of your life to start your own press. There’s the romantic nihilism of working with old metal type that will eventually wear out and become useless, and the chronic difficulty presented by beautiful but buggy vintage equipment. But when it all works the way it’s supposed to, the finished product, as well as the process itself, are sublime.

A graduate of Hartford Art School (at the University of Hartford, in Connecticut) with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting and a minor in art history, Babcock’s obsession began roughly fifteen years ago, when he took a class in letterpress printing at the Boston Center for Adult Education and found himself itching to learn more about the craft and all its eccentricities. For a little while, he was able to continue using the BCAE’s shop, but when it folded to make way for newer technologies, he found an affordable press and moved it into his apartment in Jamaica Plain, where the supremely heavy equipment has multiplied, causing Babcock to pray he never has to move out.

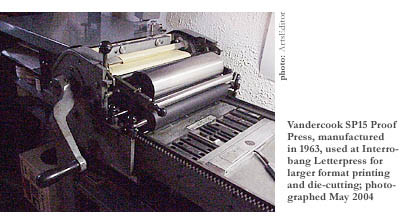

The organization of the apartment is meticulous. The shop is located half upstairs, half in the basement. The (former) dining room, upstairs, is very efficiently filled to the rafters with dozens of type cases, tools, heavy bookshelves, die-cutting tools, and the showpiece of the room—the small 1963 Vandercook SP15 Proof Press. The room smells like old wood and, more faintly, of singed metal and chemical solvents. During parties, Babcock says, “no one is allowed to stand in the dining room. I’m a little wary of adding any weight in here.”

The Vandercook press, which can pull about 300 impressions in an hour, takes up only about four feet of horizontal space in the room. Today, Babcock prints large-format or especially complex material on it, but this type of press was formerly used to make proofs for offset printing jobs. Although it’s slow relative to a larger, more expensive press, it can produce pristine prints every time. And it seems to have been made with Michael Babcock in mind—”It rolled out of the factory three days before I was born. So I was meant to own this press,” he says.

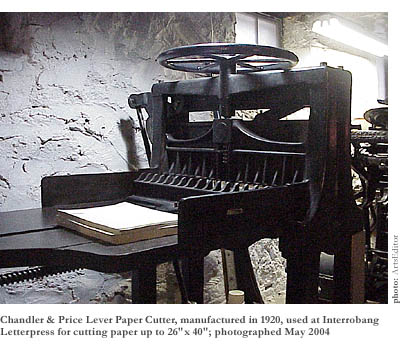

In the basement, the older, larger Chandler & Price 8 x 12 Old Style Platen Press, behemoth Chandler & Price 26″ Lever Paper Cutter, Hammond G100 Glider “Trim-O-Saw,” vintage scale, and binding/finishing area help round out the stable of Interrobang’s capabilities. The saw, made in 1950, is used for cutting leads, slugs, and rules to length, dressing their ends, mitering rules, cutting plates, and kerning and mortising type. The platen press is actually very small for its type, but it’s definitely got some presence. It has a fancy curved, spoked flywheel and weighs more than a thousand pounds. This press can do approximately 1200 impressions in an hour. It does well with smaller items like business cards and die-cuts, but it’s not equipped to print larger-format materials, a fact that has spurred Babcock to entertain the idea of getting a larger one in the future.

Babcock purchased this press (for $1) together with the paper cutter (for $150) from an older man, a former graphic arts teacher, who’d been using it to print Catholic memorial cards. But, he says, “there’s no such thing as a free kitten. I had to put new rollers on it, 70 bucks each (it takes three rollers), the motor was 200 bucks, the belt was 30 bucks, and I had to find a bigger pulley for it, so I had to source that out, that cost me 50 bucks. I had to tweak it when I got it.” Because this press was made in 1896 and still had many of its original parts, there was much work to be done to get it up to speed.

The majority of Interrobang’s work consists of wedding and event invitations, stationery, business cards, compact disc and record packaging, and posters. Because the letterpress is revered for its precision, it does its best work with type, and with detailed artwork that includes cross-hatching or fine lines. Type is the ideological center of letterpress. Its artisans respect, even revere, works of classic typography, and observe traditional rules of typesetting.

Even in an old craft, however, technological methods change with time. Newly available techniques allow letterpress projects to fulfill the modern client’s need for immediacy. The Internet, especially e-mail, has sped up processes, and next-day shipping makes it possible to get specialty papers or etched plates post-haste. Technology has also changed the very center of the discipline: type. “Some newbie letterpress artists have begun using photopolymer plates burned from negatives generated from digital files,” Babcock says. In general, the use of hand-placed metal type has declined. But Babcock is dedicated to the old way. For him, “classic hot metal type is ‘perfect’ and close to the hand of the artist.” Digital versions of classic type, which are many more steps removed from the artist’s design than their metal counterparts, can contain flaws and lack certain details found in the original metal. Issues of quality aside, though, the primary reason for Babcock seems to reside in a personal philosophy—there is too much history, too much cultural texture, to make a switch now.

And, of course, there’s literal texture as well. The work needs to be seen close-up, and touched, to be fully appreciated. Michael Babcock’s compositions are clean and uncluttered—the smoothness of the impressions on feathery paper adds visual and tactile dimensions. He often uses colored papers, linoleum blocks, and metallic inks on pieces that allow more license to experiment (such as music posters and packaging), but generally sticks with conservative colors, inks, and type for most projects. Whatever type of work his current projects entail, Babcock aims to print as close to perfect as possible, unless his client has requested a less refined look.

Babcock’s day job as a Web developer allows him to think of Interrobang Letterpress as a labor of love rather than as a financial necessity. “I could probably support myself just doing letterpress, but there are lots of snafus to this work. Doing it full-time would make the numbers much more critical.” Having money coming in from elsewhere means letterpress stays fully enjoyable for Babcock, and doesn’t enter into crisis territory—unless, say, a belt breaks on the Chandler & Price press, or a type case falls to the floor, expelling its carefully sorted contents. But minor setbacks don’t bother him—he relishes problem-solving to his core. He seems to just shrug and move on, in the meantime scheming up a seamless solution. When he finds himself without an accent mark for a certain letter, for example, he makes one—and while he’s at it, a couple of variations for future use.

What Babcock calls a “renaissance of interest in the letterpress” has bombarded Interrobang with inquiries from potential clients. He’s enlisted a friend to help with customer service in exchange for use of the equipment. What’s difficult, though, is getting interested parties to understand the value of having their piece printed on the letterpress, with its increased cost relative to other printing methods. The process is time-consuming, involves outside vendors (for photoengraving of plates, for example), and requires high-end papers and inks. But the final product has dimensionality and personality, and a certain handmade quality that can’t be faked.

Such authenticity is a hallmark of the modern letterpress, a reason it’s enjoying new attention. The practitioners still at it are in the position of “carrying the letterpress torch” from their shops in rural garages, in city lofts, and in well-worn apartments and basements like the one that houses Interrobang. The Internet has worked wonders for letterpress popularity, giving devotees a way to network and share advice and information. Through the Letterpress Guild of New England and his own search for equipment, type, and others who do good work, Babcock has found many influences and friends. John Kristensen, proprietor of Firefly Press in Somerville, Massachusetts, is his biggest mentor—”the real deal,” he says. An early influence was Bruce Licher, now located in Sedona, Arizona. Licher became well-known for his modern, stylish record covers, and earned two Grammy nominations for music packaging. There’s also Yee-Haw Industries in Knoxville, Tennessee, a multi-functional shop that produces everything from posters to greeting cards to calendars, all with a bit of color and campy style.

Despite his connections to the field, Michael Babcock is a self-proclaimed “lone wolf.” He doesn’t appear to need groups or requirements or certificates to make him, and Interrobang, secure. There’s no staff, no advertising, no fancy space, no saccharine sentimentality—just a guy, alone, at a chugging press with clacking hot metal.