“I understand.” These were the words Anthony Quinn (1915-2001) told James Lipton during a 1996 edition of Inside the Actors Studio that he wanted God to say to him as he stood before the pearly gates. It is an unusual hope for those familiar with the actor, not the man. Equally unusual is another hope he expressed, and that was to be remembered also as a visual artist.

We can attempt both of these things by appreciating his expressive artwork, thanks in part to an exhibition at the InterContinental Boston through June 2008. It is a representative selection of Quinn’s art—lithographs, bronze reliefs, free-standing stone sculptures, small sketches, and three outdoor “Monumental Works.” I also had the opportunity to visit his Rhode Island estate, where I viewed some of his work areas.

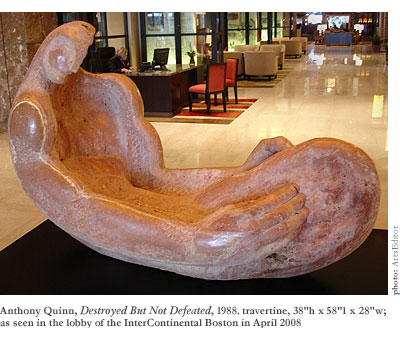

I identify Quinn the most with one of his strongest sculptures on display at the InterContinental, the four-foot long travertine Destroyed But Not Defeated (1988). Its attributes are arresting—an expressive rendering of a humanoid figure with shoulders greatly stooped forward over a concave chest and a semi-shattered, disk-like head. The muscles of the back, shoulders, and arms are grossly exaggerated and the huge right hand, tensed, invokes an unquelled might. The effect, though, struck my first viewing as not that of a person bearing weight on the shoulders, even though the inclining head recalls such a gesture. The burden is born scoop-like, as if it rested on the stomach, which, representative as the seat of sentiments, implies a struggle with emotions as well as external stress. This was Anthony Quinn—a man of great internal struggles.

I learned that this piece and others like it were initially inspired by Quinn’s discovery of an archeological site’s fragmentary sculptural remains during the filming of Lion of the Desert in Libya, in 1974. The exhibition’s press release also reveals that “while many of the pieces were missing parts, he was struck by the fact that the works’ strength and beauty had not diminished.” Destroyed But Not Defeated embodies a hallmark of the remnants of antiquity, and that is one of visible history.

Part of the beauty of an ancient work is the appearance on the work itself of the effects of time. Someone like myself may enjoy the damaged patina, the natural eroded marble, and the darkened tones from the surrounding earth in which it was buried. This adds a “natural” effect on the otherwise austere, “artificial” form of a classical sculpture. The spirit of the piece endures, suggested by the remnant, even though the physical vehicle atrophies. I find that such forms symbolically express the temperament of melancholy. Art is able to render such a temperament in a beautiful manner, redeeming its oppressive elements by way of aesthetic transformation.

Although I did not meet Quinn in life, through his works and collections it seems that he had a strong identification with melancholy, a Renaissance cult ideal for the artist. In fact, he frequently collected aged, worn works. His estate in Rhode Island is full of such. From Pre-Columbian Central American figures and 19th Century African sculpture to copies of ancient Greek fragments, a visitor is greeted with the beauty of passage, the visible presence of time, and the dolce malinconia that such objects invoke. Nevertheless, most of his own production, though often fragmented, is not aged. For example, I viewed a range of torsos and similar fragments which, unlike antique remains, retains the newness of the material (such as wood).

There are also distinct gender compositions in Anthony Quinn’s artwork. Not all artists identify with their own gender in their art. I have observed that male or female artists who strongly identify with the role of the father in a family—that of the “rules setter,” the figure of conditional love (as defined by Erich Fromm, a writer who influenced Quinn)—project themselves artistically in the male form. Both through his work, his writings, and observations from his widow, Katherine, we see that Quinn was very much a strong, traditionally defined male persona. Hence his male sculptures are expressions of his own personality, and this should not come as much of a revelation. Typically, they were muscular exaggerations, somewhat stylized, and often of just the torso region.

Likewise, the female figures are often sensual and smooth, striking empathetic, receptive positions with symbolically feminine spaces flowing through them. One I found particularly attractive in the exhibition is Aphrodite (1984). Like Destroyed, it is travertine, about three feet long; but unlike it, this is a completely smooth, fully wrought abstract figure. The figure is in a reclining position, but it is deceptively passive. In fact, the head is leaning forward and possesses inviting, friendly facial features. Almost playful is the right knee that is coyly turned inward in a defensive stance, seen from the position where a viewer would most comfortably observe her face.

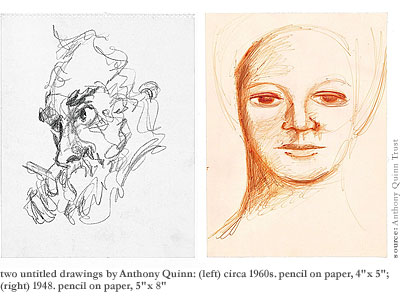

Quinn sketched frequently. At age 6, he made a portrait of the actor Douglas Fairbanks, who bought it for $25. I had the opportunity to examine some of his early sketchbooks. I was struck by the furious and free working of his pen and pencil. What dominated his style was not a careful, chiaroscuro method of condensing form through an attention to the subtleties of light, but a quick tracing of contours and key features. This method enhances mark-making and the line. With enough practice, an artist using this style may create very minimalist pieces—ones with few lines—and yet capture the personality of the subject. Quinn often did so—as in the extremely simple sketch of a woman’s face on display in the Club InterContinental lounge, its refinement attesting to the artist’s skill.

Actors tend to emphasize the capacity to seem natural in roles—an actor that is too visibly methodical is not convincing. Anthony Quinn’s creativity in the arts must have been informed by this ethic, as well as his love of personality. He rendered faces extensively, and collected masks, typically of African origins. Like his idol Pablo Picasso, he loved the purity of folk forms. Picasso, though, was trained in classical draughtsmanship and was educated in the neoclassical-dominated Paris. He had sought in non-Western “primitive” forms a creativity free of traditional conventions. Quinn’s preference for the modernist style—he emulated some of the great Spanish artist’s work—was a choice from personal identification, not so much a part of a concurrent movement.

I browsed through Quinn’s 1972 “self-portrait” book The Original Sin, expecting that it would shed light on the artist. He recounts hundreds of pages of personal experience by a verbatim rendering of every word of conversation within a limited narration of the actual circumstances in which they took place. Add to this the only “synthetic” moment of understanding of one’s own self—the narration of conversations between a psychoanalyst and a boy (who of course represents his inner self). It is the image of a man who is not only extroverted in the original Jungian sense, but pathologically so. Consequently, Anthony Quinn appeared to others as a powerful presence, intensely involved with those around him and projecting a strong ego. There is, in fact, an incredible force and energy to his work and writing. Personalities as he live a deep nightmare as well (as Quinn often confessed). When I have encountered such personalities, my own silent observing invariably encourages them to show this side. For they constantly struggle with the fluid nature of their own ego as it is immersed—and lost—in all that is around them. The creative act becomes one in which their ego is reconstituted and the artist finds solace, as the art historian Donald Kuspit has noted about Quinn. Though a burden for him, it gave Quinn the capacity to make highly expressive artwork. It is cliché, but true—the artist suffers while the viewer benefits.

I have frequently observed that a person of a certain personality will surround themselves with objects of an opposite type. I thought it would be interesting to find some aspect of Quinn’s life in which his collecting activity focused on objects representative of his opposite self—feminine as opposed to masculine, reserved as opposed to extroverted, cheerful as opposed to melancholic. I found, to my gratification, that he collected decorated eggs. They symbolize those qualities—the closed system, lightness in the decorations, and clear feminine connection. Elegantly displayed on glass shelves at his estate are over three hundred, of various origin and style. I could think of no other reason why he would collect them. Quinn enjoyed them immensely—and their luminous, playful colours found their way into his artwork, not as an expression of his self, but as a creative involvement to lift him out of the occasionally oppressive mood.

Someday, a young audience viewing the films La Strada or Zorba the Greek will perceive not just Anthony Quinn the actor, but the artist as well. He acted and created. Our appreciation of his oeuvre, and the man revealed through it, has thus far followed the order of those words: actor, then artist. Their proper sense is one of mutual flourishing.