For the first time in over twenty-five years, an American museum will be mounting a major retrospective of the full oeuvre of painter and printmaker Edward Hopper (1882-1967). The exhibition—which opens May 6th at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—occupies the awkward stance of surveying and attempting to commemorate an artist whose celebrity is far less contested than his quality. Notwithstanding, Edward Hopper will be a valuable exhibition whose potential to offer visitors a critical education will likely outshine the artist’s personal accomplishments.

It is particularly fitting that this exhibition—which will travel to Washington D.C. and Chicago after it closes at the Museum of Fine Arts on August 19th—begins its course in Boston. Among the featured works is a large collection of landscape paintings taken from Hopper’s years living in Massachusetts, including many in which he indulged a unique love affair with American Victorian architecture.

Hopper’s artistic pedigree straddles the Ashcan School of New York scene painters and other early moderns with one leg and nationalistic Americana artists like Norman Rockwell and Thomas Hart Benton with the other. Aesthetically, Hopper’s works are linked to Rockwell’s clean, candid, and stylized realism. Even further, Hopper and Rockwell both choose working-class American life as a primary subject, but their conjunction is realized on a visual level rather than a meaningful one, and a deeper interest in the American psyche belies Hopper’s artistry.

Unlike Rockwell or Benton, whose works hedge a thin boundary between kitschy sentimentality and propaganda, Hopper paints without irony or agenda, and his genuine emotional affect elevates his best paintings into the realm of a sophisticated confrontation of modern life. More pointedly, Hopper finds his thematic turf among the Ashcan artists, joining their explorations of the American modern even in spite of his apparent disinterest in the technical experimentation (generally Cubist in nature) that characterizes the works of his avant-garde contemporaries.

One of the most pervasive and substantial lessons outlined by this exhibition is the challenge of negotiating form and content. Hopper’s approach to modern art production is unique in that it derives meaning almost exclusively from content. While the most celebrated American artists of his day answered this conflict through the unified, wholly visual dynamics of Abstract Expressionism, Hopper chose instead to realign the practices of traditional representational painting within the context of American post-war culture.

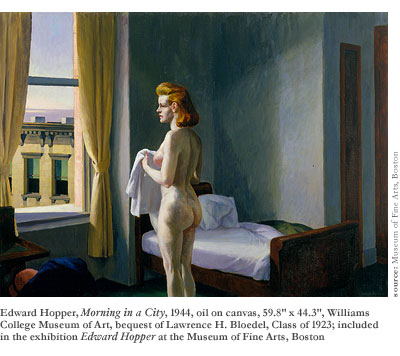

At times, it seems as though a specter of modern technique haunts the works. The general style of a painting like Morning in a City suggests Impressionism—the outlines of the buildings and their windows are too anomalous and wavering to qualify as true realism—and details like the heavy gesture and painterly coloration of the bedroom walls are deliberately expressionistic. The world of this woman’s room is more affected and touched by subtle abstraction than the world outside the window, suggesting a hidden emotional instability within her world, or perhaps a melancholic sadness.

Articulations of modern technique like these appear throughout Hopper’s works, suggesting an awareness of contemporary avant-garde practices and even a subtle technical mastery, but they are—like the inflection of the woman’s room and her figure—accessories to subjective meaning and not formal experiments in Impressionism or Expressionism. He evokes the sentimental spirit of Expressionism to imbue each setting with a mood that seems to emanate from the disposition of his figures or inanimate subjects, yet the practice remains centered about and motivated by the narrative content of a picture rather than the technical implications of applying paint to the flat, rectangular canvas.

As such, Hopper’s paintings offer a sideways glance into modernity that is all at once unique, deceptive, accessible, and incomplete. At his best, Edward Hopper presents nuanced examinations of the defining, everyday experiences of modern life.

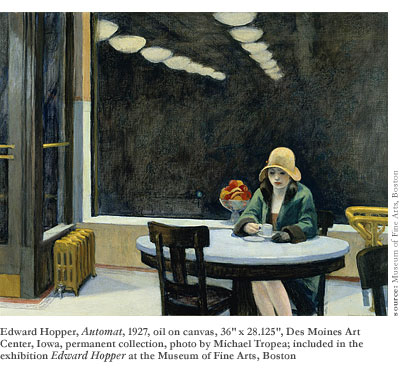

Automat—a well-known Hopper painting that depicts a solitary female nursing a mug of coffee in an empty cafeteria—uses clear visual language to confront one of the most persistent themes found throughout modern art movements: solipsistic isolation. Here again he evokes expressionistic abstraction and discoloration to heighten the ambiance of loneliness and abandon that his subject suffers, and the effect is snaring and poignant.

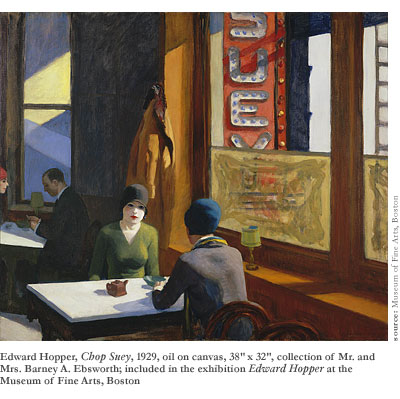

Chop Suey—which captures another restaurant scene in which two young girls keep one another’s company over tea (and presumably chop suey)—offers an even more poignant characterization of modern solitude through the women who are, even while together and in a public space, impossibly and desperately alone.

Most basically, this is why Hopper’s works feel universal—they distill expressive content into a single, easily readable moment that corresponds emotionally and logistically to the lives of modern viewers. Hopper paints situations, and even more importantly, characters with whom almost any viewer can instantly identify.

Both of these works exemplify the second, and perhaps most significant lesson to be taken from this exhibition. Hopper articulates a scrupulous blend of accessibility and aesthetics. His works don’t yield themselves up to critical discourse, yet the diversity of emotional experiences that they evoke in their viewers—despite their almost programmatically representational nature—offers a transparent and (appropriately) accessible example of how even the most static artworks function interactively with their viewers as a mutable Text.

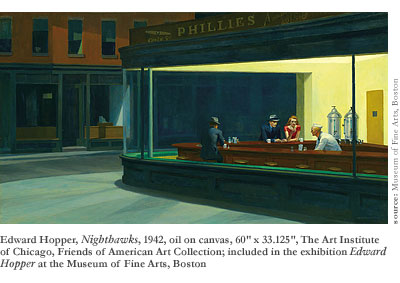

Very briefly, Text is a conceptual understanding of art espoused by a number of poststructural thinkers, principally Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault. The Text of a work is the unique meaning that one individual experiences from the symbolic content arranged by the artist. That is to say, the Text of Nighthawks (which will be unique for every viewer) is the nexus of everything thought, felt, or remembered by an individual as a result of his experience with the work. Of course, this happens with every work of art, but through his coupling of defined subjectivity and ambiguous narrative, Hopper presents a uniquely understandable example of how Text functions.

Deliberately seeded ambiguity lies at the heart of every modern project, and explains why so many find “modern art” confusing or even distasteful, as well as why Edward Hopper has enjoyed such enduring success and appreciation. Cubism—perhaps the most revolutionary movement of modern art—invokes ambiguity by representing several vistas of the same object simultaneously.

Visually, there is no ambiguity within Hopper’s works—Nighthawks is an image of four people in a diner at night. Even emotionally, his painting explores a clear and uncomplicated (though broad) emotional palette—Automat is supposed to make you feel sad and lonely as you empathize with the girl and perhaps take pity on her.

The unique brilliance of Hopper’s paintings, however, lies in the hyper-accessible ambiguity of his narratives. Each work implies a narrative history—perhaps the woman in the red dress is having an affair with the man sitting next to her at the Nighthawks diner, while the girl sitting in the Automat has been stood up by her date. Or maybe she’s a prostitute having a snack on her way home. Or a depressed salesperson for yellow hats. None (read: all) of these are true—the point is that these works demand that each user formulate a unique explanation for the emotional context that the characters—indeed the viewers themselves—have been placed in by the artist. The result is a rich yet simplistic and approachable example of Text.

The third, and most peripheral lesson found within this exhibition explores how certain artworks transcend themselves to adopt a more sweeping, archetypal identity—something one might call its cultural Text.

In this sense, Nighthawks is not an accomplished painting: it is an accomplishment. For members of a younger generation, Nighthawks is an iconographic image and idea that has rippled through situations as disparate as parodies on The Simpsons to regular recreations in cinematic scenes and Gottfried Helnwein’s painted homage that replaces Hopper’s figures with images of Humphrey Bogart, Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Elvis Presley. The painting has a cultural identity that lives as much in its recreation as it does in its original imprint, and there is a whole other Textual nexus of objects that have been produced as the direct results of independent artists experiencing the Text of the original Nighthawks for themselves.

Nighthawks might be more widely recognizable in America than most of the works by Pablo Picasso or even Jackson Pollock because its transparent subjectivity speaks directly to the American experience, its ambiguity encourages every viewer to identify personally with the painting, and it has evolved into a meta-object of American culture. No one knows what, exactly, those people in the diner are thinking, but they don’t have to ask either. They are sad. They are lonely. They are desperate and depraved and they cling to one another and to some mysterious strand of waning hope that we all have, at one point, clung to ourselves.