In seizing the helm of the 2008 Whitney Biennial, co-curators Henriette Huldisch and Shamim M. Momim assumed the challenge of “taking the temperature” of new American art, setting out to arrange a singular nexus that—at the very least—intimated the threads binding together an increasingly global art community. With the exhibition hung and the curatorial treatises published, it seems that there is indeed shared meaning to be gleaned from the superposition of the new works, though as many troubling ideological concerns arise from scrupulous examination as do elative insights. Armed and introspective, the biennial reveals today’s art as sick with indulgence, yet striving incidentally and in myriad ways towards a gesture of sublime and unprecedented coherence.

Despite a thinner roster, the 2008 biennial, which opened on March 6th and runs through June 1st, demonstrates more than any exhibition in recent memory how disparate contemporary art practices have grown. While artists explore new, more ephemeral materials and an acute sensibility for what Huldisch terms “lessness,” the loosening of ideas surrounding authenticity and authorship derived from digital production and the ever-expanding boundaries of the art object have coincided to yield an extraordinarily accommodating climate for the exploration of alternatives to meaning.

Contemporary art is approaching the limit of a decentralized creative sphere. Accordingly, where so many formal and material weaknesses are observed in new works, critical pressure cracks open their superficial, performative shells to reveal shared obsessions over time, authenticity, and the creative act, which these artists assault—perhaps unknown to themselves—with the armaments of specificity.

This singular attribute—specificity—describes at once the central successes and failures of a wide swath of artworks presented within this year’s biennial. In their essays introducing the exhibition, Huldisch and Momim respectively invoke Samuel Beckett’s sense of the absurd and the interrogation of human perception and experience of time espoused by quantum mechanics as ideal modes for approaching the terrain shared among these biennial artists. It is the artist’s charge to wrest meaning from the daily experiences of a perhaps-deterministic world that teems with activity well beyond the scope of human senses. Suitably, the curators have brought together a body of creators who have taken up the performance, documentation, replication, and transmission of specific experience as a humanistic gesture against the existential void.

Two distinct productive forces wend throughout the exhibition, struggling over an authentic claim to specificity. While Momim suggests that the significant distinction lies between works that construct a “theater of the moment” and those that investigate “a more general trend toward nonlinear paradigms of seriality,” the latter are more accurately part of a broader, stronger group of works that still “stage time,” but do so by imbuing materials with presentness and a record of action. These artworks constitute a new and rich form of spatial gesture sculpting, which contrasts sharply with weaker works that rely on theatrical co-presence to transmit meaning. Significantly, both modes are deeply invested in sculptural and installation-based efforts that attempt to create timeless experience.

Materials provide the first and most accessible way in to an exploration of specificity among the biennial artists. More post-consumer than post-minimal, an aesthetic that is at once discarded, mussed, soiled, and gnawed-upon characterizes works across the exhibition. Whether the consumptive aesthetic is articulated as a formal indicator of human presence or it develops as the product of a participatory creative act, artworks throughout the biennial share an investment in the visual language of use and decay.

Jedediah Caesar—a master of material refuse—presents several of the exhibition’s most coherent and compelling objects, including the large, rectangular beaver’s dam of detritus, Helium Brick aka Summer Snow. The work delivers an immediate sense of minimalistic geometric gestalt that gives way to reveal infinite, fractal detail in the layers of resin-encrusted debris. On the surface, the work pushes forward the now-frozen trash in an aesthetic gestures that holds visual timelessness while underscoring the ephemeral, corporeal nature of the material moment in which it was created—which, in this particular case, extends as far back as the lives of the pieces of decaying organic matter, whose advanced yet frozen degradation implies a stilled passing of time.

Image-based works—particularly those that consider the implications of replication or hover between the sculptural and pictorial realms—comprise another discrete subset of responses to the challenge of timelessness. These artists suggest that today, authenticity and timelessness are bound together in the visual documentation of specific objects and experiences.

Titled After Stieglitz, Sherrie Levine’s series of eighteen photographic replications of Alfred Stieglitz images appear as a meditation on the permeability of digital media, depicting each reproduction as a six-by-eight grid of grayscale pixels. More importantly, though, as the title aligns the images with Levine’s renown series of photographic replications After Walker Evans (which were unmodified copies of Evans’ original images), these images become records of distortion that chart the artist’s presence and disruptive actions at a given moment in linear time.

Another photographer invested in an exploration of the human experience of time, Leslie Hewitt amplifies the specificity of her records by enlarging the images and framing them in thick plywood bindings, which give them sculptural weight akin to a Frank Stella painting or Donald Judd specific objects. The timelessness of Make It Plain—like that of so many other biennial works—stands opposed to minimalist sensibilities by converting the ephemera of a singular moment into a present, immutable object—a humanistic alternative to the platonic timelessness of pure form.

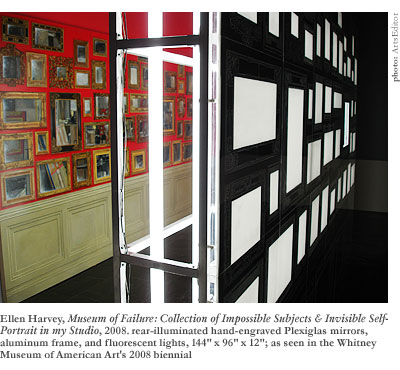

Museum of Failure: Collection of Impossible Subjects & Invisible Self-Portraits by Ellen Harvey puts specific viewer experience into necessary dialog and analogous alignment with the artist’s creative moment. A work in two parts, it presents a rear-illuminated Plexiglas mirror wall hand-engraved with forty-five salon-style frames, each of which borders a sanded-out, translucent white rectangle. The forty-fifth rectangle provides a transparent window to the painting hung behind the wall, which depicts an identical set of frames, each of which contains an image of the artist photographing herself before a mirror. In each example, the camera flash blurs and distorts the rendering of Harvey’s face.

Setting aside its oblique and whip-smart allusions to artists from Diego Velázquez to David Salle, this installation offers a composite record of the layered, nascent moments through which it developed, while mediating viewer engagement through a mirror complex that aligns each individual experience as a repetition of the artist’s own. Each viewer is ostensibly unique, yet more fundamentally functions as a timeless and authentic analog of the incipient experiences recorded by the artist.

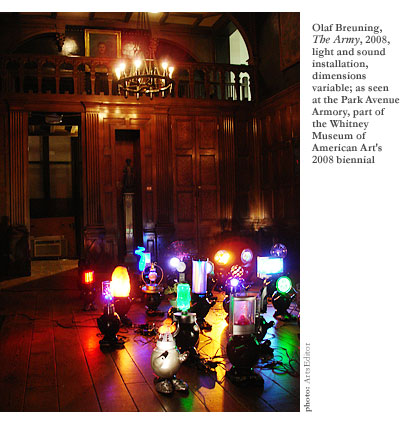

Performance art—specifically in the form of several reflexive and indulgent “expanded practices” inhabiting the Park Avenue Armory—poses a singular threat to the artists working to generate a meaningful and enduring sense of specificity. Many of the artists invested in performance explore a second aspect of Huldisch’s “lessness,” organizing non-monumental events that promote experiential specificity that depends on viewer participation and an investment in local culture. Where spatialized artworks explore time by recording experience or detaching the idea of time from linear narratives, these experiential artworks are more interested in ordaining a specific moment with passing meaning that can be uniquely claimed by the audience.

Matt Mullican’s work exhibits several of the most troubling trends observed among artists pursuing experiential specificity. While the sculptural objects Untitled (Models for the Cosmology) develop a new, timeless visual language, a questionable explanatory dependence exists between his performances under hypnosis and their extended products, Untitled (Learning from That Person’s Work). Mullican’s process involves hypnotizing himself at the beginning of a performance and allowing his alter ego—That Person—to create drawings and other works on large, white bed sheets that will later be arranged vertically in a maze-like gallery installation.

Mullican’s autonomous parasitism creates a subconscious feedback loop between performance and object that—particularly over time and repeated iterations—materially depicts individual experience and the course of one artist’s psychology. Accordingly, his installations depend on corresponding performances to create their content and describe their framing context, without which the artworks would be formless and uninteresting. This produces an indulgent series of inescapably egotistical works that are unable to transcend the conditions of the performative moment, yield no independent products that withstand critical pressure, and hopelessly defend the triteness of individual experience as timelessly meaningful.

A number of works are unconcerned with explorations of formal specificity, taking up instead social agendas and expressions that largely center about military violence or corporate hegemony. With limited exceptions, these constitute some of the most disappointing contributions to the biennial, many of whose artistic value is undermined by an oppressively zealous authorial hand.

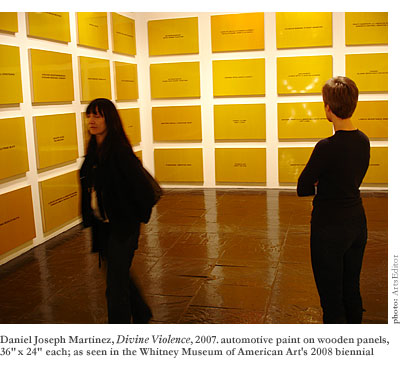

Daniel Joseph Martinez’s installation of 125 wooden panels painted with automotive gold-flake, entitled Divine Violence, exemplifies the compromises made when overt political statements overwhelm formal concerns. Filling all the walls of a peripheral museum space, the golden panels hold visual and aesthetic strength that seizes the viewer’s attention and drags slowly across the field, at once an all-over installation and minimalist environment that transmits rhythmic timelessness through a sense of its very specific, controlled, and deliberate design and arrangement.

The panels, however, are adorned with the names of violent political organizations from around the world in a brown, Comic-Sans-esque lettering. While the presentation of obliquely familiar names in readily-accessible translation might redefine the viewer’s conception of how such organizations self-identify—many monikers describe the groups as “liberators” and “protectors” acting in “self-defense”—the text detracts from the work’s visual sensibility and power to hold presentness across viewer experiences.

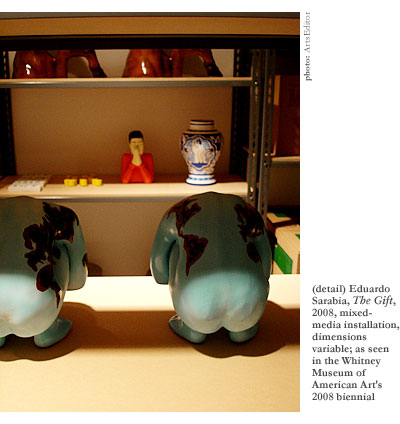

If Martinez distracts the viewer with overt political content, Eduardo Sarabia deftly wields the language of commercial mass production in The Gift, producing a work whose tongue-in-cheek social statements gild the aesthetic experience. A pantry-like installation, The Gift is a collection of porcelain and polymer sculptures that radiate a warm, playful plasticity that intimates and caricaturizes the clean, hard-edged sensibilities of advertising and product design. Viewers are invited to take with them a small pamphlet that contains commentary on each item, as well as a price list and order form for purchasing an edition of any of the works.

The Gift appropriates the visual language and market techniques of capitalism, complicating a sideways critique with earnest participation in an unavoidable—if flawed—enterprise. Perhaps more importantly, it is the only artwork in the exhibition to adopt the aesthetic philosophies of branding as an effective inroad to the creation of timeless objects and experiences—objects of serial production, the works stamp out a sense of permanence that is reinforced by the forcefully familiar experience of shopping.

If the biennial is indeed a barometer, today’s artists work in a climate that has advanced beyond statements and movements, in which they forcibly confront the base egotism and existential despondency of the creative act. At once, the artist has been charged with offering objects and experiences that hold meaning within the scope of human perception, while gesturing beyond his own boundaries towards the broader sense of time and space that science and philosophy have introduced to contemporary thought.

Carol Bove offers perhaps the most elegant and austere reconciliation of specificity with a plea to the timeless undercurrents of determinist absurdity put forth by Huldisch and Momim. Her sculptural installation The Night Sky Over New York, October 21, 2007, 9 p.m. suspends a set of identical bronze rods from the gallery ceiling in an arrangement that corresponds to the stellar cartography above the city at that precise moment in time. Hers is a work that nods towards the celestial bodies that—as Momim described in summarizing Einstein’s general theory of relativity—”produce a distortion of the space-time continuum,” yet grounds their presentation in an objectively authentic experience of place and time that is familiar to human experience. Aesthetically, the work transports viewers with a foreign, sideways approach to the cosmos that we know and understand—as the title underscores—from a singular perspective.

Art exists to invest absurd human experience with specific meaning that holds truth within and beyond the moment of its creation. Like Night Sky, the truly successful artworks exhibited within the 2008 Whitney Biennial are those that fear neither the limits of human perception, nor the necessity to challenge them in earnest pursuit of the unknown.