Canadian artist Betty Goodwin (1923-2008) and her husband Martin traveled forty years ago to Medina, Spain for the wedding of their son, Paul. While there, they journeyed to Tétouan, Morocco through Tangier. Goodwin documented her travels in photographs, especially the graffiti that adorned the walls and doorways of many Moroccan villages. She was enthralled by the raw markings, which denoted a moment passed, through remnants of paint-smeared handprints and coarsely scrawled imagery.

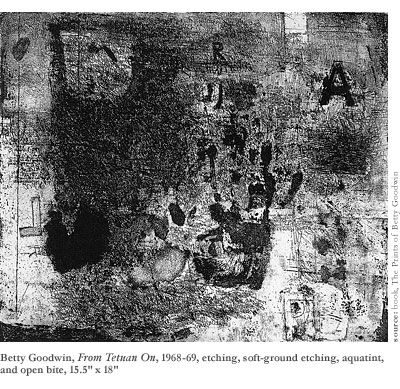

After returning to Canada, Goodwin created an etching based on her photographs, titled From Tetuan On, which depicted graffiti and handprint smudges. The aquatint print is scattered with dark, gestural marks, which pool into rich tonal areas, flickering representational displays of the letters P-A-U-L, in reference to her son, and an unidentified man’s handprint. The etching emotes the calm traces of ephemerality and the energy of a frivolous vandal.

Along with a documentation of an important moment in her personal life, this work began Goodwin’s exploration of common objects. She felt free to produce sincere Pop-inspired works at a time when derivative art drew scorn and chagrin. This, perhaps, is due to her Canadian residence, distant from the sometimes venomous American art culture. Her work is laudably without artifice, irony, and kitsch in its depiction of the common object, and it captures the slow accumulation of personal mythology and an open, modern meditation on the importance of physical objects to the people surrounding them.

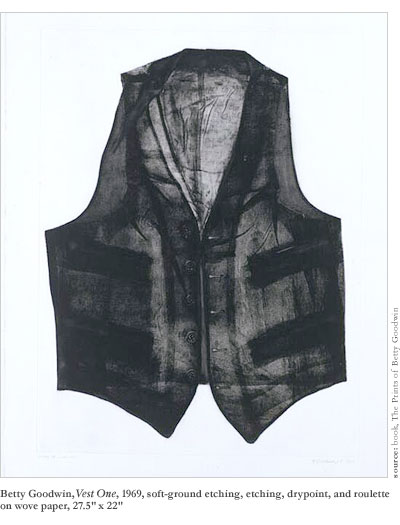

With Betty Goodwin’s passing on the first of December 2008, she leaves behind a lifetime’s work exploring the intricacies of the colloquial edifices that permeate human identity. “Through detail, Goodwin transforms a mundane object to reveal its spiritual function,” wrote critic Gilles Toupin in his 1972 article “Betty Goodwin, Tailor Extraordinaire,” for Artscanada magazine. Toupin was reviewing the recent works of the then emerging artist in her first solo exhibition at Galerie B. His assessment of the early prints displayed in the exhibit—thirteen soft-ground etchings from her Vest, Parcel, Shirt, and Glove series—crystallized the definitive spirit of Goodwin’s artwork, which will remain her legacy.

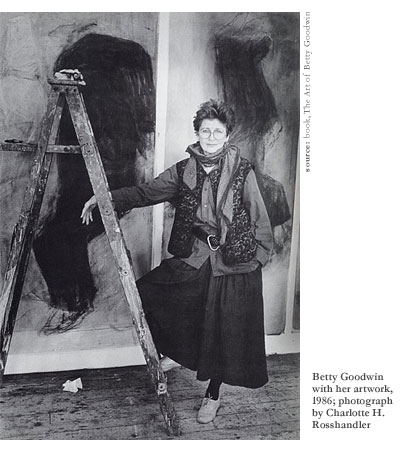

Betty Roodish was born in Montreal in 1923, the only child of Romanian immigrants Abraham and Clare Roodish. Though she studied graphic design at the Valentine Commercial School of Art and (briefly) printmaking at Sir George Williams University, Betty had no formal training in the fine arts. By her own account, she never had much talent for art-making, yet persistence carried her from broad, Cubist-inspired works of surrealism to a singular, individual voice. “Actually, I wasn’t conscious. I don’t think,” Goodwin explained in an interview with the National Gallery of Canada. “I just started. I was in my teens. I couldn’t do anything else better, but it involved very academic, very simple subjects. And I continued for years just out of sheer perseverance.”

At that moment in the broader trajectory of American art, early assemblage work and a more bourgeois exploration of modernist imagery had laid the groundwork for the Pop Art philosophy that would dictate a democratic approach to subject matter. It was this theme that Goodwin took up, and which led her to an exploration of the mundane object. Goodwin’s work with printmaking processes that reproduce photographic qualities began in the late 1960s, and took inspiration from a number of American Pop prints, in particular the lithographs of Jasper Johns. His reproductions of graffiti, handprints, and light bulbs had a marked effect on Goodwin’s attempt to develop a visual vocabulary to describe casual experience.

Goodwin’s interest in the banal also found new motivation in Robert Rauschenberg’s work with photo-serigraphy, namely Booster, a print from 1967. Encouraged by Yves Gaucher, her printmaking instructor at Sir George Williams University, Goodwin began to experiment with photographic processes, including the creation of etchings from prints on Kodalith, a translucent support. Uniform for Vietnam, a Kodalith etching of the clothing and utensils of American prisoners of war in North Vietnam, captures the essence of this technical period in her history through a meditation on a photograph taken from a contemporary French periodical. The cinereal print depicts military life in objects—striped shirt and pants, dark shirts, cloths, and blankets, punctuated by small white bowls and metal utensils. The materials sprawl across the panel, giving the striped textiles in particular the appearance of a clothed phantom. The dappled ground coalesces with the loose articles, flirting with flattened abstraction, a product of Goodwin’s physical editing that modified the original illustration, removing unwanted ground imagery and text. Where her graffiti photographs and etchings depict complex objects in the context of their environments, supported by a united sense of composition, Uniform for Vietnam shows Goodwin working more to decontextualize the object compositionally.

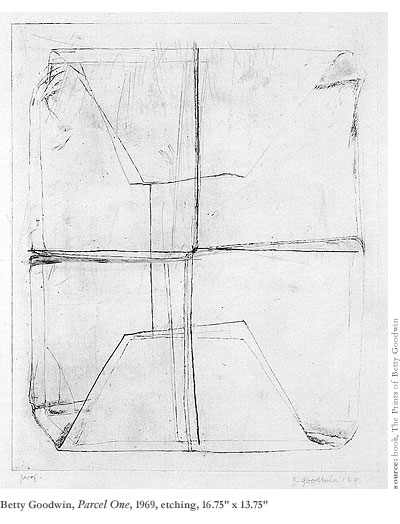

This breakthrough led to Parcel One in late 1969. It is a basic line etching of a twine-bound paper parcel. The object has been removed from its environment and reduced to near-graphic simplicity. Goodwin began working with parcel imagery after she found herself constantly exchanging them with her son Paul, who was living in Europe with his new wife. The work marked the beginning of technical shift, placing new emphasis on etching processes than on photographic ones. Parcel One, and various other pieces from the same series, contain both the mark-making of From Tetuan On, yet retain the theme of discarded objects discovered in Uniform for Vietnam. The immediacy of the piece seems to have become more important, which led Goodwin to explore soft-ground etching, a process in which objects are pressed against an acid-resistant coating that, when removed, lifts away parts of the ground. This leaves a vestigial imprint and produces detailed flat representations in the final print.

The most important breakthrough of her career, by Goodwin’s own account, came in August of 1969, when she created Vest One. The print depicts a simple soft-ground etching of a single, symmetrically arranged vest on a blank, white ground. The sensitive soft-ground process picks up the back of the vest through the front, producing an image that resembles an x-ray. The slight creases and stitching subtleties become monumental against the gloomy, aphotic patches. A flattened acuity permeates an image that festers somewhere between the abstraction of drawing and the spatial implications of sculpture. “They have acquired a certain three-dimensionality… with their hunched shoulders and flipped-over sleeves,” wrote critic Joan Lowndes for the Vancouver Sun, in praise of the seminal work.

Betty Goodwin’s notebook entries surrounding the creation of Vest One reveal intentions to bridge the Graffiti series and her sporadic moon landing prints, which took inspiration from Rauschenberg’s Booster aesthetic. But in discussing her ideas with Gaucher, Goodwin suddenly made a connection between the image of the vest and her father Abraham’s history as a tailor. (He had, in fact, founded the Rochester Vest Manufacturing Company in 1923.) She recounts how “I really only made my big connections in 1970. That was through starting a whole series of prints, starting with the Vest series.” The magnitude of this connection overwhelmed her. Finally, she felt as though she had made a major breakthrough, advancing her career in a legitimately meaningful way:

“I’ve always had a communion with objects but now more at one with my work. My life is more of a whole. If contemporary art has taught me anything, it’s brought us out of our ivory tower—right down to open our eyes and see the thereness that we are surrounded by—Oldenburg—Dine—Johns certainly freed me. Too bad I didn’t feel it earlier… Finally I’ve got myself somewhat in the flow of things instead of looking for some monumental message. I’m content to feel out the being of the thing.

I am less unsure now—more sure of my individuality… I am becoming released to be what I am. I’m beginning to find my identity.”

Goodwin went on to produce a variety of Vest prints, each examining the idiosyncratic life of discarded objects. By the mid-1970s she had begun to move on, adopting instead the Note and Tarpaulin series, which are a lateral reinterpretation of the same subject material. Adopting a wide range of two- and three-dimensional media throughout the latter part of her career, Goodwin explored in these series a number of formal issues implicit in drawing and sculpture through the subjective depth she had already established. Similar was her use of the object—even when depicting the figure, form and physicality were more important than identity. Despite individual developments over the years, it seems retrospectively clear that her early explorations of mundane objects will remain her ultimate achievement.

If the supremacy of the idea of the banal object over the individual is tantamount to Pop Art, this is where Betty Goodwin and her contemporaries part in significant ways. Her artwork submits that banal products are the witness to people’s lives, and are meaningful in that they inform who those individuals are. As Pop has been criticized for its lack of heart, Goodwin offered a bridge between its insistent, aesthetic examination of bourgeois culture and biographical earnestness, finding heart in the face of objective alienation. Even the mundane vest is not but a vest itself, and it captivates viewers as an extension of a life in which it took part. In perhaps the finest praise of Goodwin’s sensibility, Gilles Toupin surmises the same: “The human experience that passionately informs her work creates the mystery of a presence, or an absence, or both. Perhaps that is all we have to know. Her secrets defy words, they do not require them.”