Every two years, when the first scents of spring hit city air, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosts the Whitney Biennial, an exhibition of singular scope and renown in contemporary art. Second in acclaim to no festival but the Venice Biennale, it claims supreme prestige, demanding tendered care as each iteration attempts to balance a thoughtful inspection of its moment against a thirst to—in the words of Ezra Pound—”make it new.”

According to its current arbiters, “the biennial characterizes the state of American art today.” These carefully chosen words gesture towards several ambiguities confronting major institutions today, specifically the articulation of artistic meaning by curators, who administer either an accurate description of the current art climate, or an effective dictation of its future development. Sensitivity to the distance between curatorship and visitor experience—informed by an examination of their specific dialogue in the exhibition’s realization—will constitute an original reading that remains tied to the biennial’s manifold spirit of juxtaposition.

The seventy-fourth installation of the biennial opens on March 6th and runs through June 1st. It represents the experiments of Whitney curators Henriette Huldisch and Shamim M. Momim. Their project features eighty-one artists, whose selection was overseen by the Whitney’s chief curator, Donna De Salvo, and advised by Thelma Golden of the Studio Museum, Bill Horrigan of the Wexner Center for the Arts, and the independent curator and writer Linda Norden. Together, they have assembled “a laboratory, a way of ‘taking the temperature’ of what is happening now and putting it on view.” With measured self-awareness, Huldisch and Momim aim for an approachable exhibition that embraces this sense of pluralism in both structure and thematic content.

In a 1967 essay entitled “The Death of the Author,” French literary critic Roland Barthes explored a new interpretation of art experience, claiming “We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing ‘theological’ meaning… but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash.” His arguments assault the modernist conception of authorial intention, suggesting instead that a viewer’s meaningful experience with a work is a plural product of his individual interpretation of the author’s sign system and rarely in line with the artist’s will.

Today, Barthes’ postulates have been absorbed into critical discourse—indeed, the diversity of contemporary works and performance contexts has mutated to demand a networked sensitivity, forcing viewers to cast intellectual and emotional responses into dialog with a host of conflicting intentions and readings. As the curator herself has become the formal model for engagement, the 2008 biennial provides an ideal study of specific experiments with these very forces.

Chief among the questions confronting a curator are the selection of artworks and their thematic and physical organization. These concerns are complicated exponentially within the biennial, due to its open format and specific engagement with the present moment. Where a traditional exhibition has the freedom to organize itself around a singular subject (Rembrandt, blue), stylistic movement (Rococo), or historical moment (Antebellum), the biennial is obliged to speak originally to the current arts climate while surveying its full swath. “In dealing with the art of the present, there are no easy assessments, only multiple points of entry,” explain Huldisch and Momim, whose greatest challenge remains wresting coherent meaning from overwhelming diversity. “For the Whitney and our public, we hope the biennial is one way in.”

Various biennial curators have put particular solutions forward, most notably in 2006 when Chrissie Iles and Philippe Vergne adopted the poetic theme “Day for Night” to suggest a loose interpretive mode for their exhibition. An admirable risk, it was the first occasion on which the biennial was organized around such an identifiable image, and was met with pointed disapproval. Many critics felt that the curators dictated the theme of the exhibition and inductively chose artists that best articulated their vision, rather than artists who best represented other, more solvent currents in contemporary art.

In oblique response, Huldisch and Momim have approached their charge with reservation, assembling “a survey exhibition that talks about the specific terms of art-making in general by presenting a body of works overwhelmingly created for this specific event, which we curate from a body of ideas without imposing a predetermined theme on the selection process.” Despite their assuredness, the juxtaposition of these two curatorial models encourages a scrupulous interrogation of the role played by intention, and whether the denial of an overtly contrived organizational rubric will (or even could) produce a compelling and honest representation of contemporary American art remains to be seen.

Exploring the specific extensions of Huldisch and Momim’s curatorship, it is of foremost relevance that so much of this year’s biennial is site-specific. In discussing their methodology, they emphasize the research they dedicated to “casting the widest net possible,” traveling widely and refining their sensitivity to the terrain between discrete artists. Centrally, they claim to have found unity across the large body of individual creators not in medium, style, or formal project, but in an investment in locally rich culture, in an emphasis placed on social ritual and public spaces, and in a close attention to materials.

The curators intend to tap the deliberateness of this sensibility—the very source of its ability to compel—by commissioning new works that will be inextricably tied to the biennial experience. If, as Huldisch defends, “there is some engagement with form, but materials and formal concerns are more vehicles for expressing social concerns,” then the structure of the displayed objects will give way under critical pressure to a shared narrative, allowing a subtly pruned dialogue between the artworks to emerge, obviating their individual expressions. “Once you pull those themes out, the things that you’re trying to test in terms of arguments develop through a reciprocal process between the works that yields a thesis,” explains Momim. “That’s how such a large exhibition comes to take shape.” Three catalogue essays couch this thematic crux in a more detailed framework.

In “Lessness,” Huldisch contemplates a “modesty with respect to material and scope” that she has encountered throughout the new works of young artists. To her, they embrace a spirit of “anti-spectacle, non-monumental art based on local contacts and specific gestures,” and she explores trends that mark both related developments in separate artist groups, as well as events and movements that connect cities and people across nominal boundaries.

Momim, meanwhile, makes a historical treatment of the biennial participants that places their works along a trajectory stemming from a change in the human endurance and conception of time during the 1960s. Centrally, her argument holds that contemporary artists have—after careful scrutiny—abandoned the modernist narrative of linear succession in the arts, replacing it instead with a mutually informative perspective of networked history and experience.

Rebecca Solnit—a tried author but a newcomer to exhibition writing—contributes a third artifact that makes a broader commentary on the social forces she senses to be at work on the minds of today’s artists. Departing from thematic turf originally explored in her essay “Detroit Arcadia: Exploring the Post-American Landscape,” Solnit engages the topography of the American West, offering a treatment of its mythic character and associations with travel and movement that informs the curatorial stance from a position outside the realm of form, subject, and specific works.

The catalogue also contains written contributions from the eighty-one artists, complemented by visual materials depicting their relevant artworks. Unavoidably, the volume shares in the essence of the biennial’s identity—superficially, it reflects the chaotic agglomeration traversed by the exhibition’s wide swagger. Fundamentally, the catalogue is a concrete and approachable extrapolation of the post-modern survey that—though arranged with alleged deliberateness—offers more instigation to inter-textual reading by providing a frame than through the inherent properties of the art that it presents. This is probably a good thing. Visitors will find new and unique meaning throughout this exhibition, though perhaps not in the ways that its curators anticipate, which remains another good—and expected—thing.

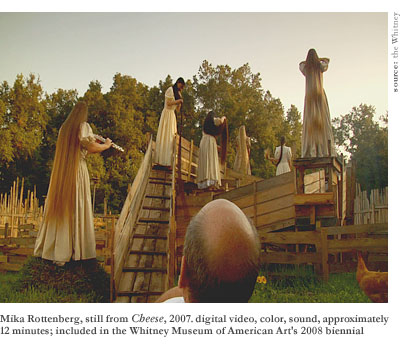

Chief among other attributes aligning this year’s artists is a penchant for performance that interrogates the relationship between the creative act and the art object. Significantly, Huldisch describes how the artists’ understanding of performance continues to broaden, including everything from musical performances to culinary gatherings as “social practice projects and interactive experiences produce and even become part of the art object. These things work to question and complicate the parameters of the gallery space.”

To wit: for the first time in the Whitney’s history, the 2008 biennial incorporates a secondary space at the historic Seventh Regiment Armory building, where a complementary series of performance events, temporary installations, and other public programs will feature the alternative works of more than a third of the exhibiting artists. While several individuals make tentative forays into an unexplored medium, seasoned performance artists including Mika Tajima/New Humans, Gang Gang Dance, and Mario Ybarra Jr. constitute the majority of the participants.

The curators hope that these additional artists will highlight the ephemeral themes shared by performance- and object-based works that are central to perceiving the meaningful and deliberate vectors that describe artistic and curatorial intentions against interactive viewer experience. “The exhibition is largely about process and the idea of process,” remarks Momim, whose discussion of the weight carried by sculpture and installation in this biennial suggests that the static works are less invested in making object impressions than in forcing a particular physical negotiation of gallery space.

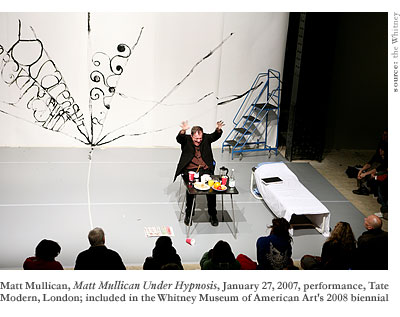

Matt Mullican presents a particularly unique contribution to the performance pastiche, making what he promises will be his final appearance as “that person,” his alter-ego under hypnosis. His work highlights an extraordinarily important theme for the biennial that the Armory events are intended to augment—the hermetic, autistic, textual drawings he makes while hypnotized are integrated into his gallery artworks, providing a tangible link between the ephemeral and object-based spheres that the biennial strives to suggest.

More so than any other exhibition, the biennial must be met at once with an open-minded and critical appraisal of the unexpected moments visitors draw from the human assemblage. Put another way, the curators have perhaps misappraised their exhibition’s worth—the biennial is less “one way in” than a dynamic nexus, whose potential net worth as a vehicle for exploring contemporary art has barely been intimated.

Notwithstanding, several specific concerns remain unaddressed. It is unclear whether proper consideration has been spent reconciling the ethos of locally minded creativity within the structure of the Whitney Biennial, or contemplating the distance between the proclaimed philosophical core of artists working within that sphere and their acceding “non-monumental” art to an institution of magnitude.

Authenticity remains a tenuous subject for the critic’s appraisal, but here it seems unavoidable, as these works decry formal deliberation and depend instead on a declaration of physical human interaction. Artists are regularly lambasted for their participation in the economic and institutional apparatuses that support the arts, yet there is no fault in seizing that agency so long as it is taken up with the same integrity that defines the artists’ work. Authenticity does not depend on abdication—rather, it reflects an internal harmony among an artwork’s philosophical infrastructure, its physical realization, and its transmission. The greatest test confronting the 2008 Whitney Biennial will scrutinize its artists in search of that same consistency, with the exhibition’s own claims to authenticity hanging in the balance.