There is a subtle difference between shock and surprise. For many, the raw reverberations of continuous shock exhilarate, while the sweetness, bewilderment, or astonishment of surprise fails to satisfy. Over the past few decades, contemporary art has become increasingly extreme and often uses its power over our senses to lay claim to our minds. To be genuinely and pleasantly puzzled is becoming rare. Art that surprises is enigmatic. It beckons us to sharpen our focus and discover elements of beauty, intrigue, and complexity. It does not repel us, assault us, or stun our sensibilities. Instead, we delight in its wonder.

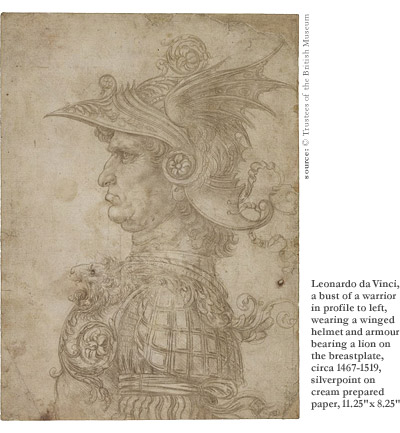

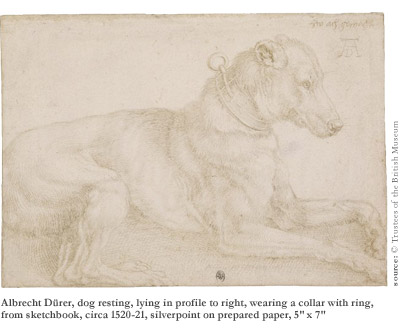

Contemporary silverpoint drawings are surprising. You may ask, “Silverpoint? What’s silverpoint?” Indeed, the intrigue of this archaic technique may be, in part, due to its unfamiliarity. Though little is known in contemporary times, silverpoint’s history began centuries ago, in the 1300’s, when Italian artist Cennino Cennini wrote one of the first art history technique treatises, Il Libro dell’Arte (or The Book of the Art). Cennini stressed the importance of drawing as the foundation for an artist’s technical advancement and specifically dissected the process of creating the proper ground for using silverpoint. His instructions prescribe burning the bones of chickens and mixing the resulting ash with a carefully prepared color. This dry powder was then mixed with saliva to moisten it and allow it to stick to the paper’s surface (most likely parchment or vellum). Only with such preparation, which left the paper abrasive enough to pull flakes of metal from the stylus, would silver (or other metals such as copper) be able to imprint its thin, precise, indelible line. The line is not created, however, simply by dragging the silver over the paper. The visible mark only appears when the minuscule flakes oxidize with the atmosphere. Old Master artists such as Da Vinci, Dürer, and Rembrandt embraced this medium and used the slight, but shimmering, line to draw delicate, precise, intricate portraits.

After the Renaissance, artists rarely used silverpoint, an indication that artistic trends mirror changing social dynamics. The process of preparing the ground could take hours or even days. The discovery of red chalk allowed artists to work faster, reflecting society’s growing focus on speed—of preparation, creation, and reproduction. Antithetical to this trend, silverpoint requires time, forethought, and the knowledge that the final product can never be reproduced. As the world quickened the pace of progress, the laborious process of silverpoint was left out of the race for the “shock of the new” (to borrow a phrase from Robert Hughes). It was discarded in favor of faster, user-friendly techniques.

During the mid- to late-20th Century, however, silverpoint began to infiltrate contemporary artistic culture again, creating a dynamic intersection between tradition and innovation. The level of detail and length of time, once a deterrent, were attracting contemporary artists who found solace in the very process that had long been rejected. Although they embraced the labor-intensive method, these contemporary artists were not merely mimicking the realist style and subject matter of their predecessors. Instead, their work explored modern notions such as minimalism, conceptualism, and abstraction, shedding new light on both the medium and the artistic concepts, twisting both into original and innovative models.

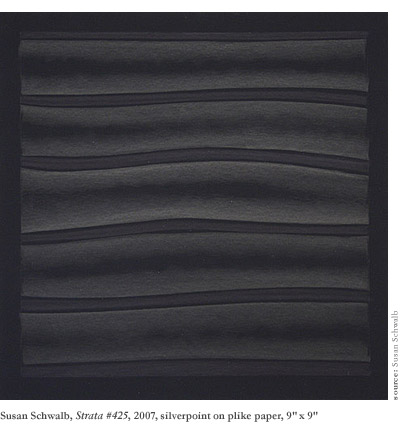

“[Artists] want to bring people into their worlds,” says Susan Schwalb, a leader in the modern silverpoint movement. Based in the Boston area, Schwalb has been experimenting with silverpoint since 1974. Her introduction to the medium was not inspired by the Old Masters, but rather by a fellow artist who encouraged her to try the silver stylus because of her desire to work with very fine lines. Silverpoint proved more appealing than the fine ink pens she previously used, and inspired Schwalb to work primarily in the medium for her extremely delicate, glowing drawings, which have attracted much deserved attention, garnering invitations to numerous gallery and, increasingly, museum exhibitions.

Schwalb’s world requires her viewers to observe slowly and “look really close.” When faced with her artworks, there is no question that they demand this type of attention. Everything beyond the frame blurs as our eyes try to penetrate the thin, meticulously drawn lines with the hope of discovering the source of the works’ energy. The marks left by the stylus are lighter and more luminous than those of graphite, and unlike most common drawing utensils, the impressions are uniform in width and intensity. In pieces such as Strata #425, depth and movement can only be created through a conscious and deliberate process of layering the lines. By placing them so close together, she creates a unifying energy and inner luminosity, and projects a cohesive, undulating abstract form.

Using silverpoint in conjunction with other elements such as paint, smoke, and fire, the ethereal glow that emanates from Schwalb’s drawings makes us wonder if there might be something living within her works, and our inability to comprehend just how this spiritual presence is achieved is both exciting and puzzling. Our unfamiliarity with silver as an artistic medium and its ability to deliver such simple beauty encourages us to savor this new visual sensation and ponder the mechanics of the technique.

Schwalb’s ability not just to catch our eye, but to capture our imagination, is a welcome surprise. Her works do not force themselves upon us, loudly declaring their agenda, purpose, and meaning. They are calming, visually subtle drawings that allow us to consider them in our own way, patiently waiting for our own thoughts and feelings to complete them, to bring them more fully to life.

But there is something haunting as well. Drawn with silver and other metalpoints on a black background, Horizon #4 is particularly compelling. The blended lines appear to float above the page, allowing the image to seem almost tangible within our own space. We are tempted to reach out and touch it, but something elusive keeps us at a distance. It is not a violent push or an abrasive barrier, but an invisible boundary that never allows the viewer to completely understand how the works are created, a secret that remains safe with the artist. Silverpoint is a medium beyond our common experience. In a world where information is freely and easily obtained, to discover something that hovers just beyond our comprehension is a wonderful sensation.

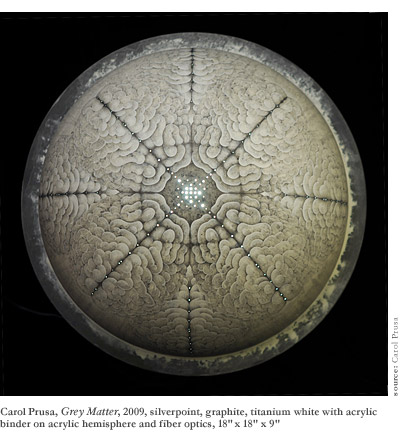

While Susan Schwalb’s work seems to be suspended above its paper or panel ground, Carol Prusa’s works actually do extend into the viewer’s space. Intricate, mesmerizing patterns are drawn on acrylic three-dimensional hemispheres dotted with fiber optic lighting details. While the fiber optics may seem incongruous with the simplicity of silverpoint, the two exist harmoniously. One might suspect that the lights would overwhelm the complex web of delicate designs, but they do not. Rather than detract from the drawings, the lights heighten their luminosity, reappointing and readjusting focus by literally shedding new light upon their surface. Prusa has redefined both ancient and contemporary traditions, quieting the digital and enabling the silverpoint technique to compound its visual intensity.

Prusa’s interest in the medium was sparked by time she spent in Florence, Italy, where she was introduced to some of the classic drawings, but her practice has extended far beyond the type of work she observed. Whereas the Old Masters sought to accurately preserve and replicate their subjects (most often portraits or studies of animals), Prusa’s works are filled with numerous allusions and metaphors, which excite and inspire the viewer to think about the past, present, and the future.

Prusa admits she is obsessed with “figuring things out,” and, particularly in Grey Matter, she has figured out how to synthesize an ancient artistic medium and modern technology. The resulting harmony underscores the conceptual aspect of her work. As suggested by the title, Grey Matter represents the anatomy of the brain. The elaborate pulsating waves of silverpoint design clearly indicate the complex physicality of the brain, while the quivering pinpoints of light evoke the electric activity of the mind.

Both of these artists have been working in silverpoint for most of their artistic careers, and both note that their work is beginning to attract greater acclaim, especially in the past several years. From the sharp increase in the number of silverpoint exhibitions, one may conclude that its unique qualities are beginning to penetrate and creep through the cracks of our censure to strike a chord with the public. A traveling exhibit, which I recently visited during its stop at Connecticut College, exclusively showcases silverpoint artists, including Schwalb and Prusa, as well as Marietta Hoferer, Cynthia Lin, and Natalie Loveless.

But why, after centuries of neglect, is the appeal of silverpoint increasing at this point in history? Established trends often dramatically shift in a crisis, and it may be that the social, political, and economic events of the past few years have brought us to a tipping point, triggering a reaction against ideas we’ve held in high esteem—speed, technology, mass production. Perhaps we are beginning to reexamine our values and return to a more natural pace and sense of humility. Maybe we are finding some relief and comfort in tradition. Whether the larger art world will mirror this shift is to be seen. But for those of us searching for something different, silverpoint offers an answer. A small pocket of artists blend tradition and innovation, mix mystery with meditation, and, above all, sustain luminous, pure beauty. Their work reminds and reassures us that the world of contemporary art is delightfully, and surprisingly, expansive.